It was a beautiful spring morning when the homeowner made her daily stroll down the long driveway to her mailbox. As always, her dog loved to go with her, sniffing the air for new scents as he walked alongside her. She gathered up the mail and walked back up the driveway, shuffling through the envelopes to see if there was anything of interest. As she approached the house, she unconsciously glanced back to be sure the dog was still nearby. He was nowhere to be seen, but she wasn’t concerned since the dog would often wander into the woods in the rural area where they lived. She called his name but he didn’t return. Growing concerned she started back down the driveway, calling his named louder and louder. Finally he emerged from the woods across the street, wagging his tail and carrying something in his mouth. She figured it was probably a squirrel or maybe a dead bird he had found. As the dog got nearer she was horrified, there was a human hand dangling from its mouth!

OK, it turned out that it wasn’t a human hand, but it certainly looked like it to her. She called the local sheriff’s office and the deputy who arrived had a hunch it wasn’t human. But to follow protocol and verify what it really was, he bagged it up as evidence and submitted it to the state crime lab. The forensic experts at the crime lab realized it wasn’t human but contacted the local natural history museum to make a positive identification; it turned out to be the skinned-out front paw of a black bear. Bears and humans have similar bone structure in the hands and feet. We both have five long bones in each hand and foot, and we have the same number of phalanges (finger and toe bones). It’s easy to see how they can be confused at first glance.

Right front paw of a bear (l) and a plastic human hand skeleton (r) (Ohio History Connection photo).

So why are skinned-out bear paws lying about in the woods!? In areas where there is hunting of black bears, hunters will generally skin the animal in order to keep the hide. They want the claws attached to the hide, so they will skin out the feet. Parts of the carcass may then be scattered by scavengers and then turn up in unexpected places. The first thing to look for is if the distal (last) phalanges are present. That’s the bones at the end of the fingers and toes and is inside the claws. These bones and the claws will stay with the hide. If these last phalanges are missing from the “hand” then it’s almost always a bear.

Contributing to the field of wildlife forensics is one way that museums can use their natural history collections to assist law enforcement. But what is “forensics”!? In a nutshell, it’s applying scientific methods and techniques in the detection of crime. It’s hard to turn on the TV these days and not see a show about forensics. However these shows are mostly about forensic anthropology, or the application of anthropological knowledge to the law. There are many other academic fields that contribute to legal cases, such as forensic psychiatry, forensic geology, and even forensic accounting – which is used to discover financial crimes. So in our case we’re applying knowledge of zoology and anatomy, and using museum vertebrate skeletal collections, to assist in investigation of wildlife crimes.

“But how can animals commit a crime?” I was once asked this when beginning a school presentation on the subject. Obviously animals aren’t the perpetrators of the crime, but are the victims. There are numerous laws protecting wildlife. Notable examples are the Endangered Species Act which protects species vulnerable to extinction; the Migratory Bird Treaty Act which protects native bird species; and the Marine Mammal Protection Act which protects whales, porpoises, dolphins, walrus, polar bears, and other marine species. In addition to these federal laws, there are state and local wildlife laws which also help to ensure that animals and even plant species will survive for future generations to observe and enjoy. Poaching and smuggling of animals or their parts are significant components of wildlife crime, and this is an area of forensics where museums can be of great assistance.

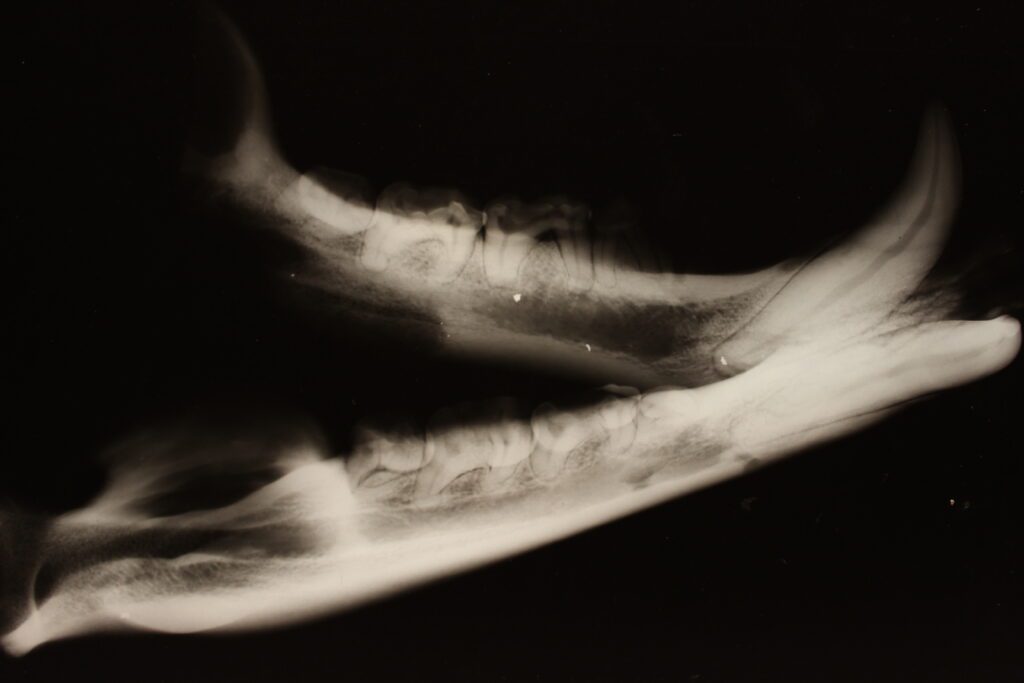

Radiograph of a black bear mandible. Bright white spots inside the left mandible are lead fragments, which indicate that the bear was shot (Ohio History Connection photo).

In a previous museum position, I was able to consult on a large number of wildlife forensic cases. In addition to the usual cases that arrived at the state crime lab, such as the bear paws and domestic mammal bones that were confused with human bones, I was able to use the museum collection to help in some other more interesting cases. Here are a few examples:

Part of the Ohio History Connection vertebrate skeletal collection (Ohio History Connection photo).

As we’ve seen, museum skeletal collections are a critically important resource for identifying skeletal remains of wildlife from criminal investigations. We already use the skeletal collection at the Ohio History Connection on a regular basis to identify bones found from a number of contexts. Animal bones come to us from archaeological sites, from paleontological sites – which often contain bones of extinct species, and from bones that people find digging in their gardens or farm fields. Identifying bones, especially fragmented pieces, is very difficult or often impossible to do by just looking at 2-dimensional illustrations in a book. So our skeletal collection, which is already used for research, exhibits, and educational programs, can also be used as a key tool to aid in wildlife investigations. In general terms, most of the work of a museum involves service to the public. By using the museums’ collections to aid law enforcement and help protect wildlife is yet one more way that museums are valuable to the community.