I recently heard a story about women in Ukraine. In anticipation of a Russian invasion, they are learning self-defense and other methods to organize against the incursion. It made me think that women, no matter where, have always stepped up and done whatever necessary to protect their homes and defend and support their country. In the United States, during World War II, this was evident with women serving at home and abroad. According to the National World War II Museum website “… by the end of the war, over 350,000 women wore American service uniforms. Though they did not serve in combat roles, 432 women were killed and 88 taken prisoner.” 18 million women also served on the home front in a variety of ways: selling war bonds, supporting the American Red Cross and filling thousands of war-industry jobs to keep production going to supply the military with the ammunition, jeeps, planes, tanks, landing mats, and myriad other goods necessary to fight and win the war.

In the Steel Museum (Youngstown Historical Center of Industry and Labor), we have a picture of some of these home front women in our gallery. We call it our “Rosies” or “tin flippers.” The black and white image features about a dozen people, women in front and men behind them. The women worked in the mills during the war and served as inspectors who monitored steel quality as it came off the line. What makes the image so interesting is that the women wear very little safety equipment. They worked in such a dangerous environment among steel manufacturing and production jobs and were often injured. This was before the establishment of OSHA and the speed with which the U.S. entered the war necessitated that some women work without the requisite safety equipment. These women inspected finished sheets of metal. They examined the steel for its size, thickness, and defects. While this doesn’t sound like a dangerous job, they were inside active steel mills without protective headgear, steel-toed shoes, goggles, or hearing protection. The aprons they wear are cloth, and the only protection they have are the glove-like devices on their hands.

The museum’s tin flippers.

The term “Rosie the Riveter” encompassed all of the women working in war-time production. Women worked as riveters, in air plane factories, as ship builders, and bomb makers. They worked in gender-segregated sections with male supervisors. Many died as a result of the hazardous conditions in the mills. Locally, many women worked for Republic Steel, Youngstown Sheet and Tube, Youngstown Steel Door, General Fireproofing, Truscon, US Steel and others companies. They worked in all departments, were patriotic about their jobs and supported the effort by selling and buying war bonds, growing Victory gardens, and donating to the various scrap and recycling drives.

When interviewed, some of the women described their work as pleasant and a way to contribute to the war effort. Carrie Peterson, a tool tender at Youngstown Sheet and Tube, stated that her war production job was her first time in a mill and “…I find the work very interesting…” and “…Since we can’t do our work on the battle front we’ll do it right here at home.” It sounds as if she wanted a more active role on the front lines but was restricted by mores of the day. Evelyn Anderson, working in the Machine Shop of the Campbell Works (YST) stated that “working here has been an experience I never thought I would have. I enjoy the work and I’m glad I can help my country.” Mrs. Edna Irwin, a laborer in the Seamless Tube Dept. (YST), commented that “I’m glad to work so I can buy more stamps and war bonds.”

An advertisement from Republic Steel, seeking women workers during the war effort.

Dorinda Tabor first worked as a Shear Helper at General Fireproofing before moving to her job as a crane operator at US Steel, McDonald Works from 1942-1944. When reminiscing about her work, Mrs. Tabor said “I liked the experience [as a crane operator but] I didn’t like the idea of having to do it because of the war….” Of her coworkers she mused “I think the women found out they were able to do more than keep house and raise kids… [and] realized they were very capable.” Elma Beatty worked as a Pipe Inspector in the Electric Weld Mill #1 at Republic Steel. When interviewed, she stated that the work was demanding: “It was hard and it was cold. Many times, I used to think to myself, ‘oh my God, I should be home with my two kids,’ but then I realized, every night I would listen to the news to see just how America was making it out and at first, we weren’t, so everyone pitched in.”

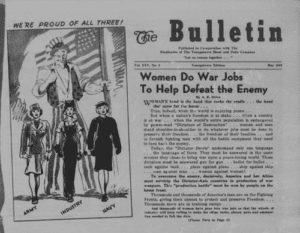

A 1943 article in the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Bulletin details women’s war work.

The war took a toll on all Americans and many lost loved ones to it. Once the war ended, American society dictated that women resume their roles as wives and housekeepers. Some women were happy to relinquish their long hours of work on the factory floor for working in their homes while others preferred the good pay and comradery found in the mills. Other women liked working in “interesting” jobs that gave them feelings of empowerment and self-worth. They liked that they worked as a team for a common goal and actually accomplished something significant at the end of the day. Others were widows or divorced and had families to support. They needed these good paying jobs to survive. Unfortunately, soldiers returning home filled the factory jobs and resumed their patriarchal roles in society and at home. While women were glad that the war was over and the soldiers returned, many were not as pleased to return to their mundane, boring, low-paid jobs in domestic service, sales, and office work. At this time, they didn’t have a choice and were summarily dismissed as returning service men took their jobs. This transition back to civilian life was difficult for the men and women who worked, fought and served during the war years. Women felt as if their contributions were not recognized or appreciated and felt they lost the respect and self-sufficiency that such responsibilities engendered in them. It would take a while, but we would see such issues being addressed during the Civil Rights Movement as well as the Women’s Liberation Movement in coming years.

For more information on content mentioned here, please visit the Youngstown Historical Center of Industry and Labor’s website and digital archives found here.