Guy Gibbon’s Archaeology of Minnesota: the prehistory of the upper Mississippi River region is a wonderful synthesis of Minnesota archaeology, but what does it have to do with Ohio archaeology?

Guy Gibbon’s Archaeology of Minnesota: the prehistory of the upper Mississippi River region is a wonderful synthesis of Minnesota archaeology, but what does it have to do with Ohio archaeology?

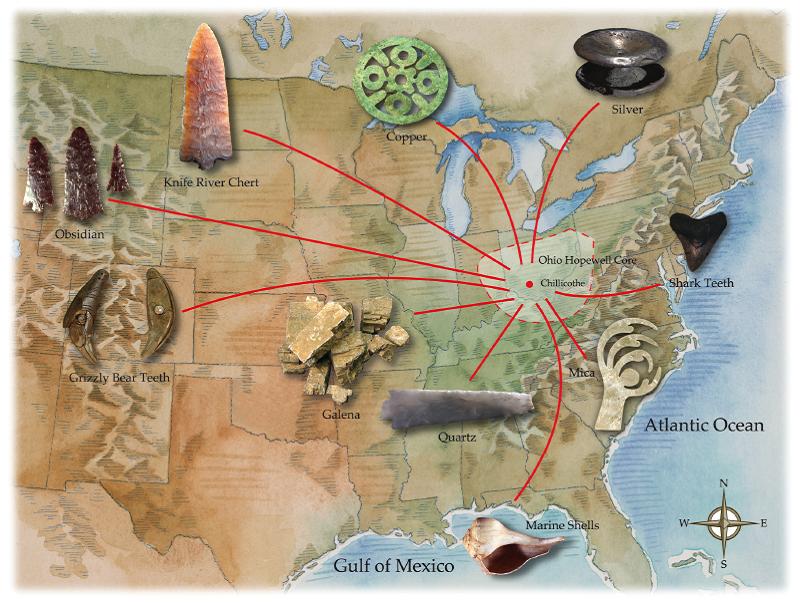

Hopewell Interaction Sphere — trade items or pilgrim’s offerings?

In my May column for the Columbus Dispatch, I compare the cultural trajectories for the precontact American Indian cultures of Ohio and Minnesota. One important connection I don’t mention in my column is the Hopewell Interaction Sphere, which encompassed much of eastern North America, including Minnesota. Gibbon provides a list of exotic raw materials and cultural traits that demonstrate the Middle Woodland people of the Mille Lacs region in central Minnesota “were involved, if only peripherally, in this political-religious phenomenon.”

Large platform pipe from Ohio’s Tremper Mound determined to have been made from Minnesota catlinite

The list of exotic raw materials found at Minnesota sites includes copper, Knife River flint, and obsidian. Although there is no specific mention of Ohio materials, such as Flint Ridge flint, being found in Minnesota, Ohio Hopewell sites definitely include artifacts crafted from Minnesota pipestone. Thomas Emerson and his team from the University of Illinois’s Program on Ancient Technologies and Archaeological Materials have determined that 17 of the 105 fairly intact pipes in the Tremper Mound collection are made from Minnesota catlinite. So, the people of Minnesota and Ohio were aware of each other on some level. The nature of their interactions remain to be determined, but I have argued elsewhere that it was more than merely trade. Instead, it was, as Gibbon notes, part of a political-religious network. Another important reason for considering Gibbon’s wonderful book regardless of what state you’re from is his application of Lewis Binford’s frames of reference approach to the study of hunter-gatherer lifeways. Gibbon provides a model for how this “complicated and difficult to comprehend in detail” approach can be simplified and used to inform our understanding of a state’s prehistory. I hope some Ohio archaeologist takes up the challenge of using this approach to improve our understanding of Ohio’s rich past.

Finally, as I point out in my Dispatch column, Gibbon makes a powerful case for the importance of archaeology in addressing the potentially catastrophic environmental and social problems facing our world: “‘If poverty and environmental deterioration are under cultural, and therefore human, control, they could be significantly reduced, or even eliminated, by intentional cultural design and change’ [John Bodley]. Can we take the risk of not trying to understand with urgency these large-scale transformations and the processes that underlie them? Though Minnesota was at the periphery of great changes in social complexity, an understanding of the social processes at work in the state before historic contact remains no less important, for their understanding will reveal how and why people live the way they do in particular historic circumstances. It is essential, then, that we value the archaeological record of the state and work diligently to protect it. It is an irreplaceable part of world heritage whose close examination seems increasingly to matter.”

Brad Lepper

For further reading: Gibbon, Guy 2012 Archaeology of Minnesota: the prehistory of the upper Mississippi River region. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.