Thoughts on the Archaeoastronomy of Alligator Mound

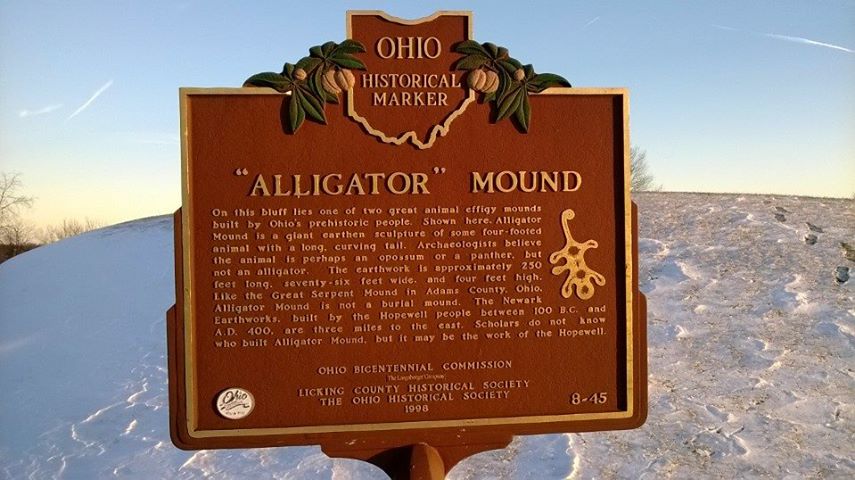

Alligator Mound crouched atop this bluff overlooking the Raccoon Creek Valley in Granville, Ohio.

by Guest Blogger Jeff Gill

On a hilltop overlooking the valley within which sit the Newark Earthworks, there perches an earthwork over 200 feet long, an effigy of sorts with a name that is a mystery in its own right, and a one-time stone mound with stories all its own now missing, but hidden in plain sight nearby. Alligator Mound, if it were the only ancient monument in Licking County, Ohio, would probably get more attention. The work of curator of archaeology Brad Lepper has shown the likelihood that the name connects back to a creature from Eastern Woodland American Indian traditions, the Underwater Panther known as Mishepishu to the Ojibwe: a creature whose jaws are strong and don’t let go, living in the pools and slackwater eddies of the rivers and creeks where American Indians fished and gathered, but with connections to whirlpools stirred up by the long curling tail it brandished, and to the lower world beneath the surfaces of our everyday lands. This creature, this Underwater Panther, described to early European settlers, would have evoked a creature never seen in these northern waters, and not really well outlined in our mounds shape, but the common mythic description might have sounded like an alligator to pioneer people, and the native interlocutors would have likely shrugged and said sure, an alligator if asked if that was what they had described.

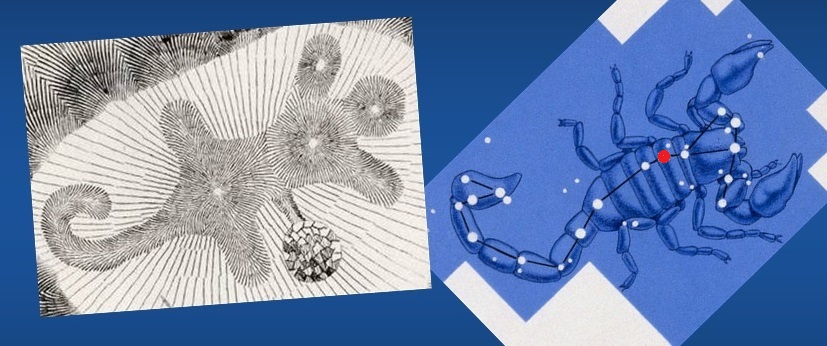

The Squier and Davis (1848) map of Alligator Mound compared to the constellation Scorpio, which has been linked to the Underwater Panther in some American Indian traditions.

Mishepishu, the Underwater Panther, was also associated with the summer constellation we call Scorpio: claws to the west, a curl of long tail behind dangling easterly. Summer is when this assemblage of stars, with Antares the glowing red heart, peers above the southern horizon, and summer is when American Indians would have been out wading and fishing and collecting in the watercourses, warning the young of caught feet and undertow in swirling currents. The shape of Scorpio is dramatically echoed in this bluff-top mound, another connection. The head of this creature, whatever the name, points to the southern end of what today is Mount Parnassus in Granville, to the southwest. The axial alignment of head, shoulders, spine, and most of the tail points to a spot on the southwest horizon which is astronomically not terribly significant, a point that is sunset about a month before, and a month after the winter solstice, a universally significant marker for ancient peoples anywhere in the world.

The solstice and equinox sunrises and sunsets align with the spiral at the tail’s east end and the four footpad platforms. In this image the setting sun casts a shadow across the Alligator at axial alignment minus two or three days. Photograph by Jeff Gill

The main axis of the Alligator does not appear to be aligned to anything in particular, but its at least interesting to note that when the sun begins to rise to the south of the heads orientation, you are in the darkest, shortest days of the year; whereas when it starts to rise back to the north, or to the right of the centerline, you have no doubt at all that daylight is longer even though there are cold nights and snowy ice-laden days ahead. Is the meaning tied to that visceral reality? And then there is the eastern end of that long tail. The tail is long, and like Scorpio, it curves around. Some suggest that a possum is one analogue to this mound, because they also have prehensile tails and a pouch within which their young are hidden and branching out from the midsection of the Alligator is a ten foot wide ridge leading to the remnants of a stone platform. The story goes that most of the stones from this altar were sledged down past todays St. Edwards Catholic Church to become the foundations of Tannery Hill, a private home near Clear Run that may be the oldest standing structure in central Ohio, let alone Licking County, going back to 1806 or so. Possums aside, that spiral draws the eye, and evokes comparisons. Ohio’s other effigy mound, the better known Serpent Mound in Adams County, ends in a spiral, and to the east as well. And if you stand at the end of the spiral, whether your own shadow or a staff in hand, you cast a line on the Vernal Equinox that at sunrise arcs across the body of the Alligator, south of the former stone altar, and cuts right across the northwest, right front forepaw of the effigy. In fact, the same exercise at sunrise will show a very rough alignment from the spiral center to the right rear paw platform at the winter solstice sunrise, or to the left rear paw platform at the summer solstice sunrise. And you get equally intriguing results at sunsets, as is astronomically always the case, echoing back in the opposite directions.

Appropriately enough, the lost paw at the southwest corner, which collapsed after it was undermined by a stone quarry dug below it in the mid 1800s, does not seem to have any alignment of clear astronomical significance but then again, neither does the central axis of the figure, unless you presume a meaningfulness to this ancient work in the first place.

In those classic words of scholarly archaeology, further research is needed!

Jeff Gill is a program assistant at the Newark Earthworks Center and interpreter for sites around the Licking County region.