Beginning on January 1st, 2025, The Octagon Earthworks will be open to the public daily for the first time in over a century.

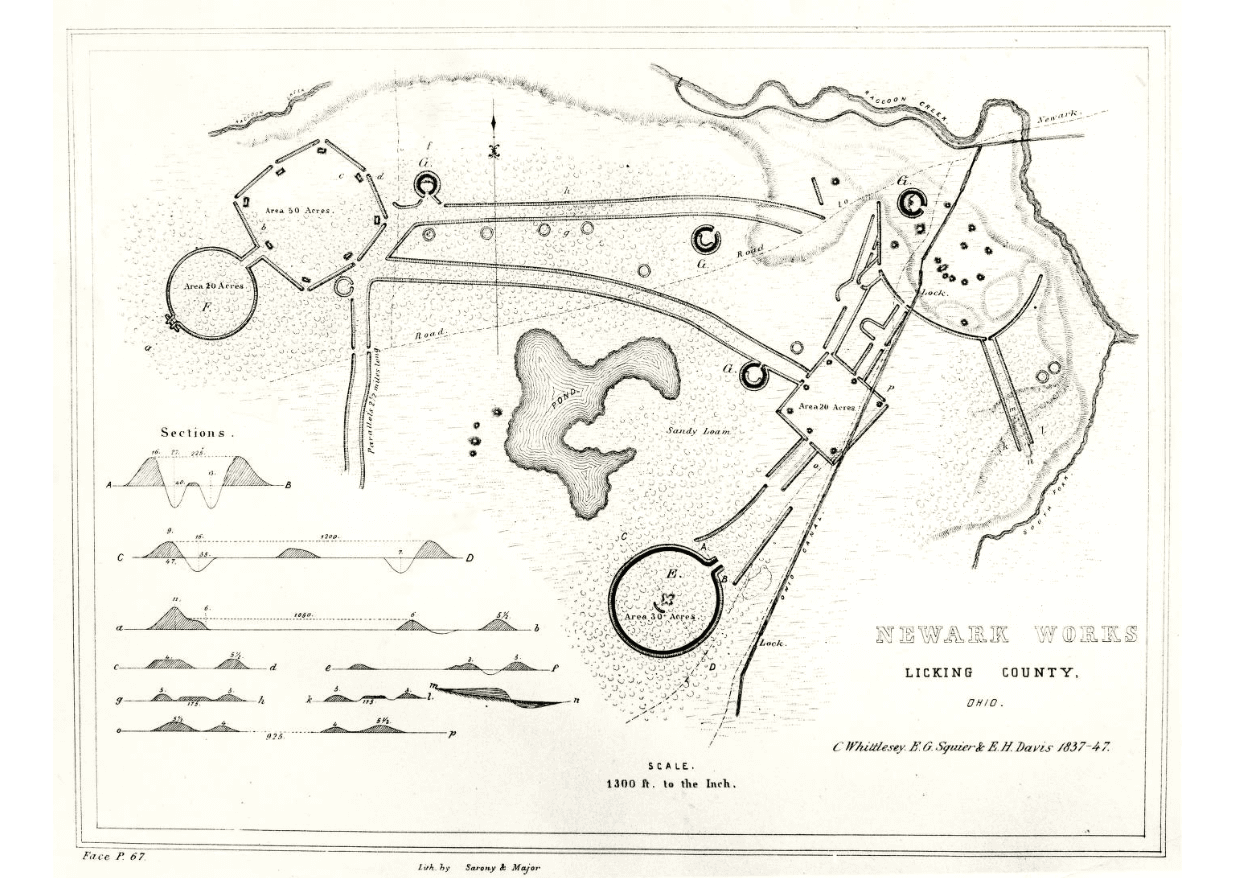

Newark Works, Licking County, Ohio, from Squier and Davis 1848 | reproduction accessed via Ohio History Connection

What is known today as the Octagon Earthworks is a preserved section of geometric earthworks, including the Octagon, the Observatory Circle, and the Observatory Mound, once part of the larger Newark Earthworks complex. American Indians constructed the Newark Earthworks between the banks of Raccoon Creek, the South Fork of the Licking River, and a glacial pond during the Middle Woodland period, between 100 BC and AD 400 (Lepper 2016). As the name of the earthwork suggests, they built the monumental Octagon with eight precisely planned earthen walls. Among other elements of architectural grammar, they aligned the Octagon and the accompanying Observatory Circle with the northernmost moonrise occurring every 18.6 years (see Hively and Horn 2013).

The Northernmost Moonrise at the Octagon, 2024 | Ohio History Connection

The Octagon Earthworks is one of many monumental earthworks built by American Indians during the Middle Woodland period. People of the Hopewell Culture constructed earthworks throughout the Ohio River Valley. The term Hopewell is used to describe the many different American Indian peoples who constructed these monumental earthworks, crafted certain styles of pottery and stone tools, ate certain kinds of foods, and lived in small communities moving about the landscape seasonally about 2200 to 1500 years ago. The name comes from a Euroamerican landowner whose nineteenth century farm encompassed one of monumental earthworks. So, Hopewell does not describe any single Tribe or nation, but rather a lifestyle based on the material culture various groups of people chose to make.

People of the Hopewell Culture traveled across North America and brought special objects, like mica, obsidian, galena, and ocean shells, back with them. Alongside these objects, they crafted intricate and specialized tools from a local stone called Flint Ridge chert. This type of chert was preferred because of its high quality and beautiful colors, ranging from pale grey to green to blue to pink to orange to red. People of the Hopewell Culture gathered together to construct the Newark Complex just about ten miles from the outcropping where Flint Ridge chert originates. It is no surprise, then, that some Flint Ridge chert has been found at the site of the Octagon Earthworks. At some point in the site’s history, someone crafted a tool with chert quarried from the nearby Flint Ridge. They left behind fragments of stone once the tool was complete. These fragments are curated by the Ohio History Connection, documenting pieces of this person’s experience at the Octagon during the Middle Woodland period.

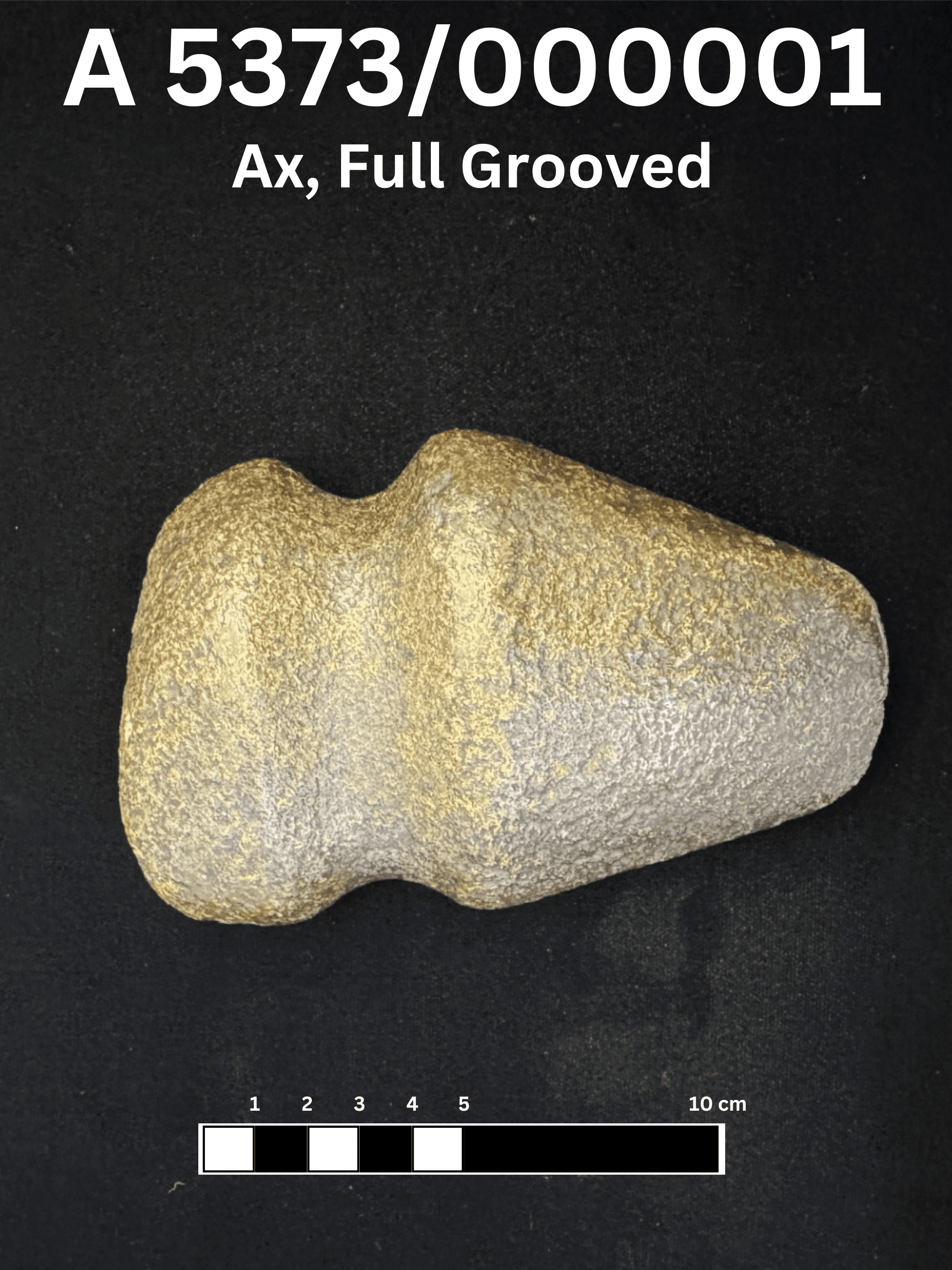

Full-grooved ax from Raccoon Creek below the Octagon (A 5373/1) | Ohio History Connection

Other object stories from the Octagon Earthworks began before the earthworks were constructed. People of the Hopewell Culture built the earthworks on a landscape already imbued with meaning and material from past generations. Sometime during the Archaic period, 9000 to 3000 years ago, someone crafted a full-grooved stone ax to use in their daily life. They eventually lost or discarded the ax near the banks of Raccoon Creek. The ax likely rested there as generations passed up and down the creek, even as people gathered on the creek banks during the Middle Woodland period and climbed the embankment to construct the Octagon just above. It remained there until the twentieth century and is now curated at the Ohio History Connection. Like the fragments of Flint Ridge chert, the ax represents pieces of people’s stories tied to the Octagon Earthworks.

These few objects are the only Pre-contact objects curated from the Octagon Earthworks. Remaining collections come from Post-contact historic activities tied to the unique site management history. Euroamerican settlers established the city of Newark very close to the Newark Earthworks complex. As the city grew, urban sprawl destroyed much of the complex, but parts of the earthworks, including the Octagon, remained relatively intact. The Octagon became the site of the Ohio State Militia (later the Ohio National Guard) in 1893 and remained the State Encampment Grounds for military purposes until 1908 (Lepper 2004). The property was then deeded to the Newark Board of Trade, which leased the site to the Moundbuilders Country Club in 1910 (Lepper 2004). The club opened in 1911 (Lepper 1991a).

The Octagon property was deeded to the Ohio History Connection, then known as the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, in 1933 in the midst of the Great Depression (Lindley 1945). At the 47th Annual Meeting of the Society, Secretary Galbreath reported “the conditional acceptance of deeds for two tracts of land in Licking County, including the famous prehistoric earthworks popularly known as the “Fairground Circle” and the “Octagon,” both in the immediate vicinity of the city of Newark” alongside staff losses and budget cuts related to the financial crisis (Galbreath 1933:344). While the Great Circle became Moundbuilders State Park, the Society maintained the existing lease to the Moundbuilders Country Club. Moundbuilders Country Club has remained the lessor of the site for the entire time the Ohio History Connection has owned the property. The majority of archaeological collections from the Octagon are remnants of nineteenth and twentieth century recreation, including bottle glass, skeet targets, and golf tees, recovered from construction projects.

It is unusual for one of these earthwork sites to have mostly escaped archaeologists. The Calliopean Society of the Granville Literary and Theological Institution excavated the Observatory Mound in 1836 (Lepper 1991b), but the unique history of site management at the Octagon Earthworks following its use as the State Encampment Grounds limited subsequent archaeological work. Yet, the objects cared for in the archaeology collections at the Ohio History Connection are testaments to the enduring significance of the landscape, the daily lives and architectural brilliance of people of the Hopewell Culture, and the complicated stories intertwined at the site of the Octagon.

Sara Polk, Curator of Archaeology

Eight earthwork sites, including the Octagon Earthworks and the nearby Great Circle, were awarded world heritage status in 2023. The collections from the Octagon Earthworks speak to the human creative genius of the American Indians who built the earthworks and contribute to the stories that are now recognized as world heritage. Learn more about the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks here.

In 2024, the Ohio History Connection reached a settlement to buy out the country club’s lease on the property. The Octagon Earthworks open with full public access for the first time on January 1st, 2025. The range of collections from the site are the remnants of the activities of many different peoples navigating the same landscape over thousands of years. Next time you visit the Octagon, think about the archaeological collections and the stories they may tell in conjunction with the monumental architecture of the earthworks.

January 1, 2025, 11am-2pm

Octagon Visitor’s Center

125 N. 33rd St., Newark, OH 43055

Galbreath, C. B. 1933. The Report of the Forty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 42:341-357.

Hively, Ray, and Robert Horn. 2013. A New and Extended Case for Lunar (and Solar) Astronomy at the Newark Earthworks. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 38:83-118.

Lepper, Bradley T. 1991a. A Brief Report on the Archaeological Integrity of Octagon State Memorial/Moundbuilders Country Club. Report on file, Ohio History Connection, Columbus.

Lepper, Bradley T. 1991b. Early Archaeological Investigations in Licking County, Ohio. Ohio Archaeologist 40(4):6-7.

Lepper, Bradley T. 2004. The Newark Earthworks: Monumental Geometry and Astronomy at a Hopewellian Pilgrimage Center. In Hero, Hawk and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South, edited by Richard F. Townsend and Robert V. Sharp, pp. 73-81. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Lepper, Bradley T. 2016. The Newark Earthworks, A Monumental Engine of World Renewal. In Newark Earthworks, Enduring Monuments, Contested Meanings, edited by Lindsay Jones & Richard D. Shiels, pp. 41-61. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville & London.

Lindley, Harlow. 1945. Chronology and Roster of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 54:247-256.

Squier, Ephraim G. and Edwin H. Davis. 1848. Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. Bartlett & Welford, New York.