INTRODUCTION

Every year Ohioans find teeth from a variety of large mammal species. These generally wash out of the banks of streams or rivers, are uncovered when excavating for a pond or drainage tiles, or occasionally are found on the surface of the ground. Enamel is a very hard substance, and teeth will often survive after becoming separated from the skull or jaw or even after the bone has eroded away. Teeth are relatively easy to identify compared to fragmented skeletal remains, and this can allow us to determine what species are present in the state today and from Ohio’s Ice Age past.

This guide will provide you information on the variety of teeth that are found in the state, and hopefully help you identify what you’ve found. A note of caution though: If you find the tooth of an extinct mammal such as mastodon or mammoth in the ground in its original position, contact a museum or university geology department before removing it. This will help to preserve any information that can be learned from the sediments it’s preserved in. Though enamel is a hard substance it can also be brittle and removing a tooth from the ground could cause it to crumble.

For more information on collecting natural history objects, including relevant legal issues, see my previous blog post “What is it? – Identification of Natural History Objects” here.

NO DINOSAURS IN OHIO!

Often when big teeth or bones are found, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that they must be from a dinosaur. But no dinosaur remains have ever been found in Ohio. In fact, the rocks that might contain dinosaur remains were either never deposited in Ohio or have long since eroded away.

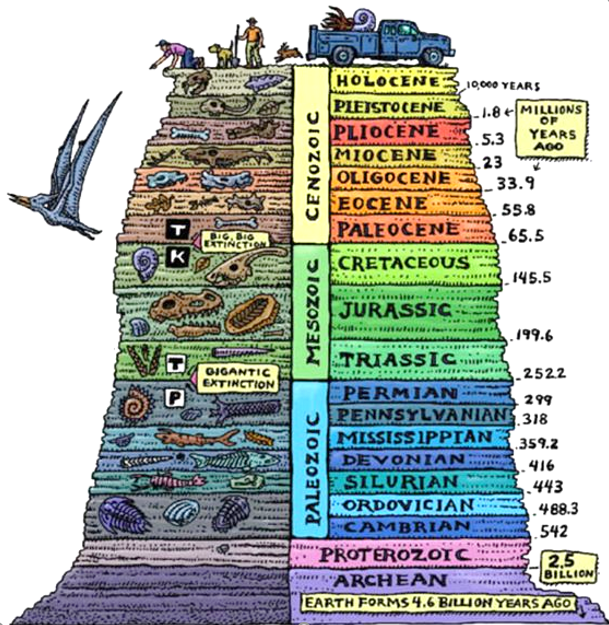

But we have an amazing diversity of other fossils in the state. Ohio has abundant invertebrate fossils from much of the Paleozoic Era, which dates from about 540 to 250 million years ago. We also have a rich record of fossils from the Pleistocene epoch (the most recent Ice Age) dating from about 11,600 years ago and older.

A geologic cross-section of the earth. Rocks from the Triassic through the Pliocene are not found in Ohio.

WHAT IS NOT A TOOTH

Before we look at the variety of mammal teeth that can be found in the state, let’s look at some things that are not teeth but can be easily mistaken for them. Due to their tooth-like shape, fossil horn corals are often mistaken for teeth. These are a group of solitary corals that lived in the Paleozoic seas and one animal (polyp) lived in each horn-shaped skeleton. Horn corals can be distinguished from mammal teeth by their outer wrinkled surface and by the distinctive internal ridges, called septa, clearly visible at the wide end of the skeleton. Also, horn corals are mineralized due to their great age in the hundreds of millions of years while the fossil mammals found in Ohio are in the thousands of years old – not nearly old enough to become this mineralized.

A horn coral from Ohio, Zaphrentis.

Another Ohio horn coral, Streptelasma.

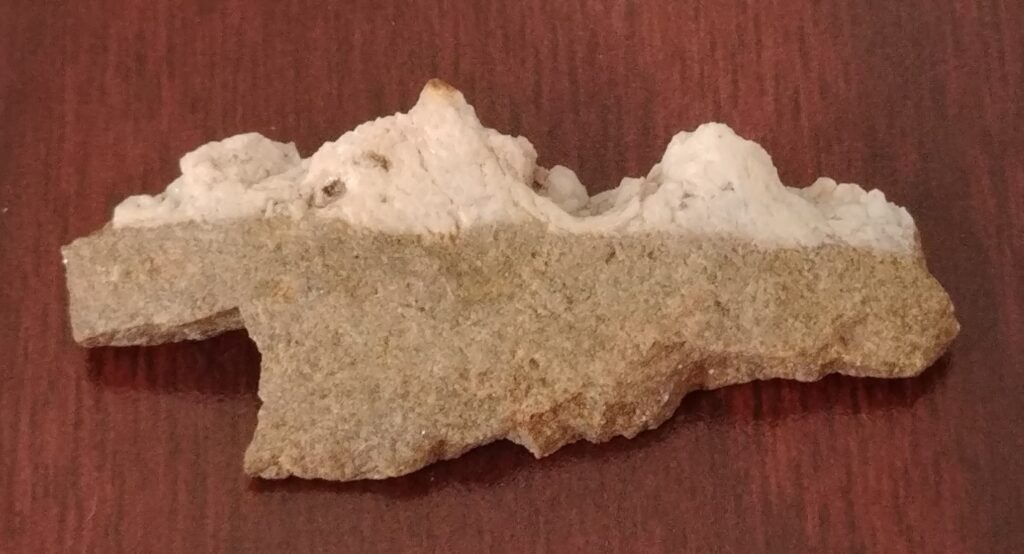

Rocks or minerals can also break down and weather until they closely resemble animal teeth. In the first example below, the rock was broken in such a way that the bottom part looks like the bone of a jaw and the lighter mineral above has pointed edges that resemble teeth. The second specimen is the mineral calcite, and the shape resembles a tooth. I was sure both of these were teeth until I picked them up! But in both cases there is no structure that would be found on a tooth, such as enamel, dentin or roots.

It’s not teeth, just a rock!

This is a mineral, not a tooth.

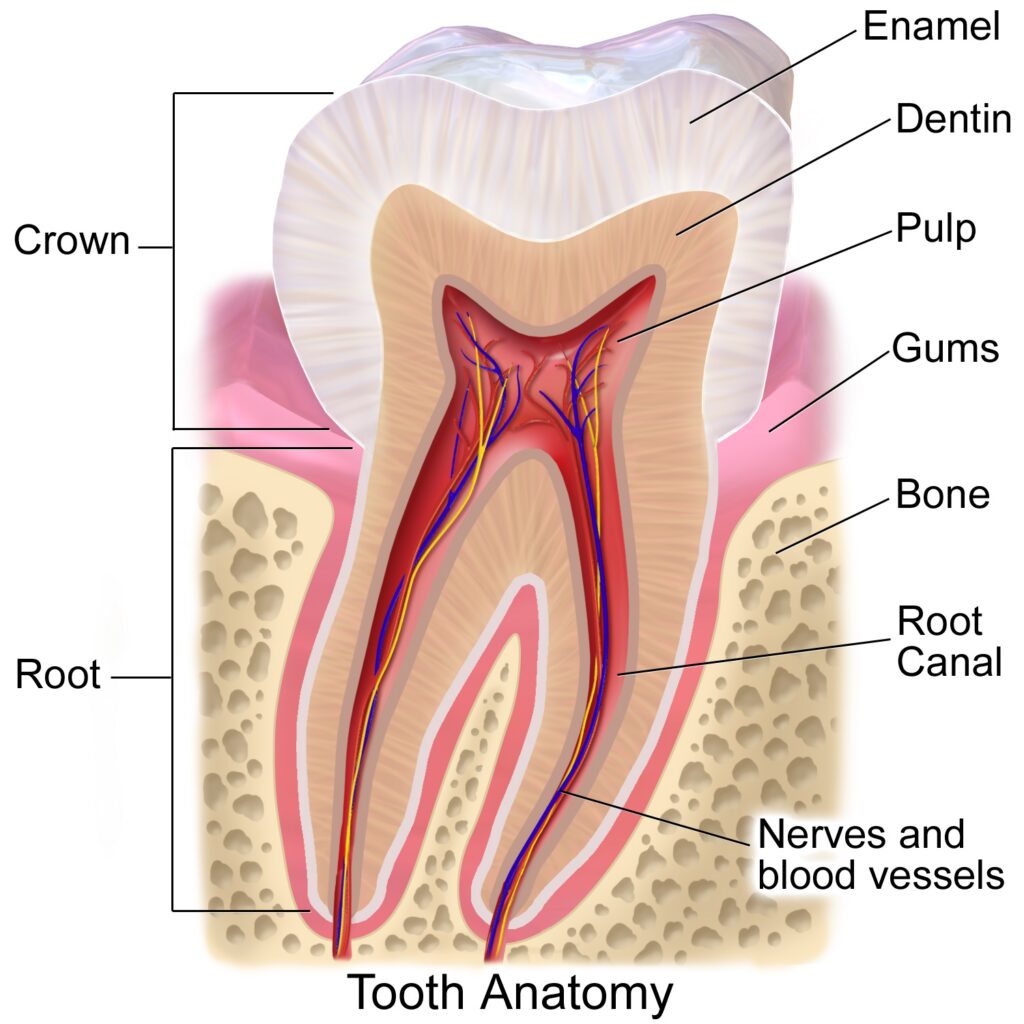

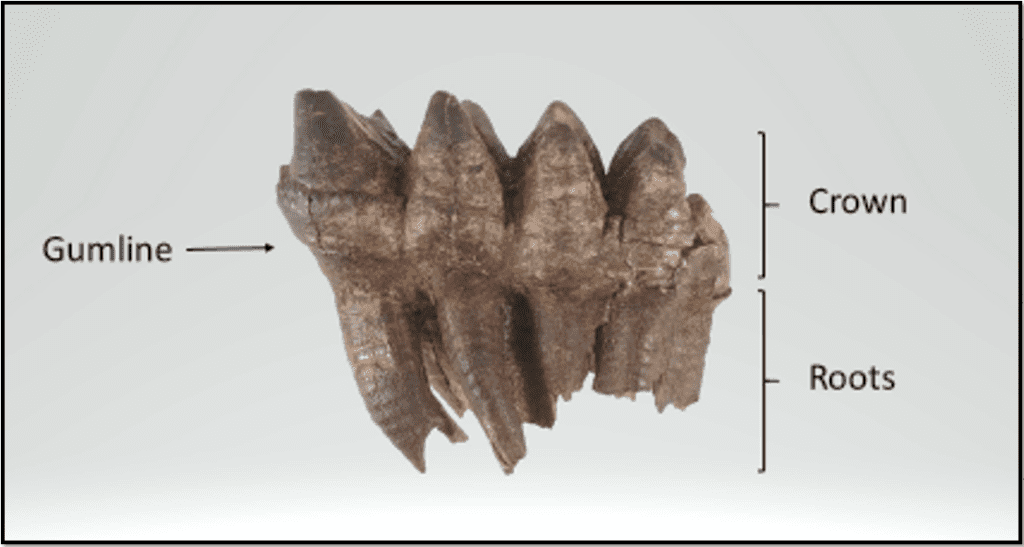

ANATOMY OF A TOOTH

Before continuing, let’s look at the structure of a tooth. The terms here will be used in the descriptions of the teeth in the next section. A typical tooth has two main parts: 1) a crown, consisting of enamel over a softer bone-like material called dentin and 2) roots, made up of dentin covered by a thin layer of cementum, which acts to help anchor the tooth in the bony socket. The chewing surface on the crown of a tooth is called the occlusal surface. The gumline is where the top of the gums would be in a living animal. Cheekteeth primarily refers to the premolars and molars, which run along the cheek as opposed to the canines and incisors which are in the more anterior part of the mouth. The term anterior means towards the front of the mouth while posterior means towards the back of the mouth.

Anatomy of a tooth (Wikimedia Commons).

EXAMPLES OF LARGE MAMMAL TEETH

If you feel that what you found is most likely a tooth and not one of the imitators, and you’re familiar with the basic parts of a tooth, let’s take a look at the variety of large mammal teeth, starting with the largest. This is a brief overview of the common, larger teeth that are likely to turn up in Ohio. Note that there can be wide variation in the appearance of a tooth within a species, depending on age, wear, diet, and individual variation. If in doubt, contact a museum or university for assistance.

Mammoths (Mammuthus sp.) roamed Ohio near the end of the Pleistocene period, along with their distant cousin the mastodon. Mammoths were grazers, feeding on grasses and sedges, and their teeth reflect their specialized diet. The enamel visible on the occlusal surface of their teeth is arranged in rows of plates that extend down through the tooth to the roots. This provides a tough grinding surface for processing coarse silica-rich grasses and is a very long-lasting tooth surface. No other large tooth will have this distinctive pattern of enamel ridges.

Woolly Mammoth – Mammuthus primigenius. Upper molar.

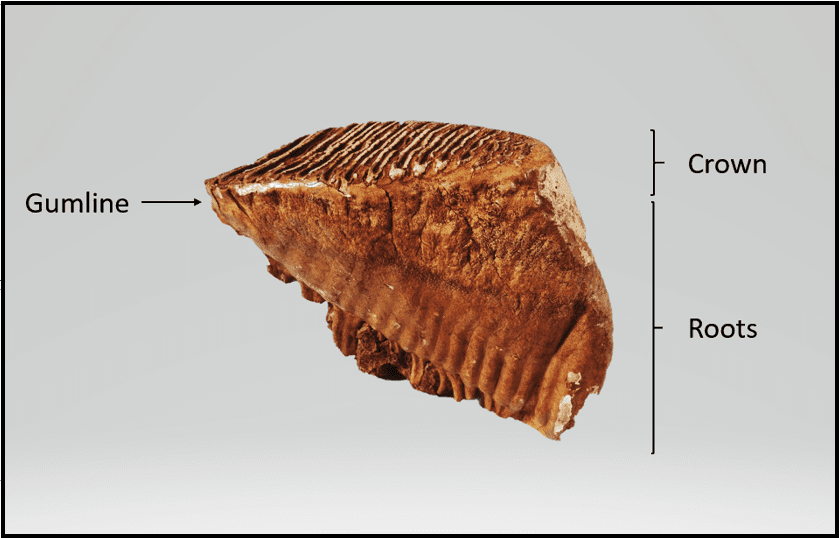

Mastodon (Mammut americanum) teeth have cone-shaped cusps covered with enamel, perfect for their browsing diet of leaves, twigs, spruce cones, and even aquatic plants. Note that the enamel covering on the tooth is on the crown only and doesn’t extend down through the tooth as in mammoths. The cusps in mastodon teeth will become more flattened as the tooth wears down with use.

American Mastodon – left upper third molar.

American Mastodon – occlusal view of the crown (roots missing) of left upper third molar. Note the conical shaped susps.

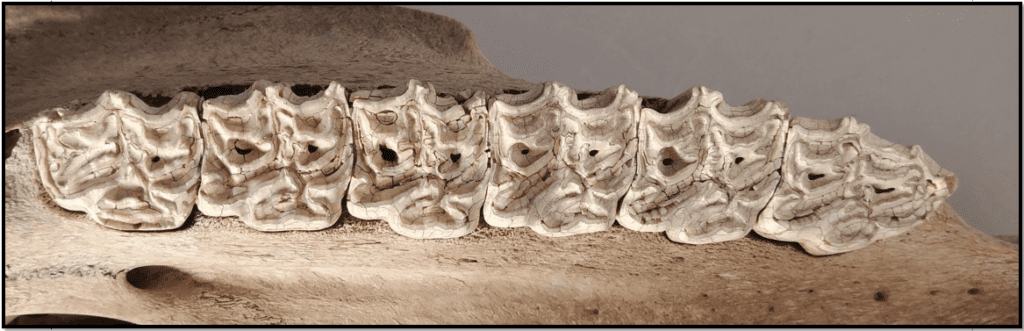

Horses (Equus sp.) lived in Ohio during the Ice Age but were extirpated from North America shortly after the glaciers left. They were then reintroduced to North America by Europeans at about 1500. Horses have high-crowned (hyposodont) premolars and molars. This means that the crown of the tooth is high and extends well below the gumline, an adaptation for a grazing diet. The crowns of horse cheek teeth tend to be more square or rectangular in shape. Another distinctive trait in horse teeth is a complicated enamel pattern of raised enamel ridges (lophs) of which some are oriented transversely across the crown surface.

Horse – Equus caballus. Upper right toothrow; anterior is to the right.

Horse – Equus caballus. Toothrow of left mandible; anterior is to the left.

Horse – upper left molar/premolar. Note the high crown and square shape of the tooth. Scale is in centimeters.

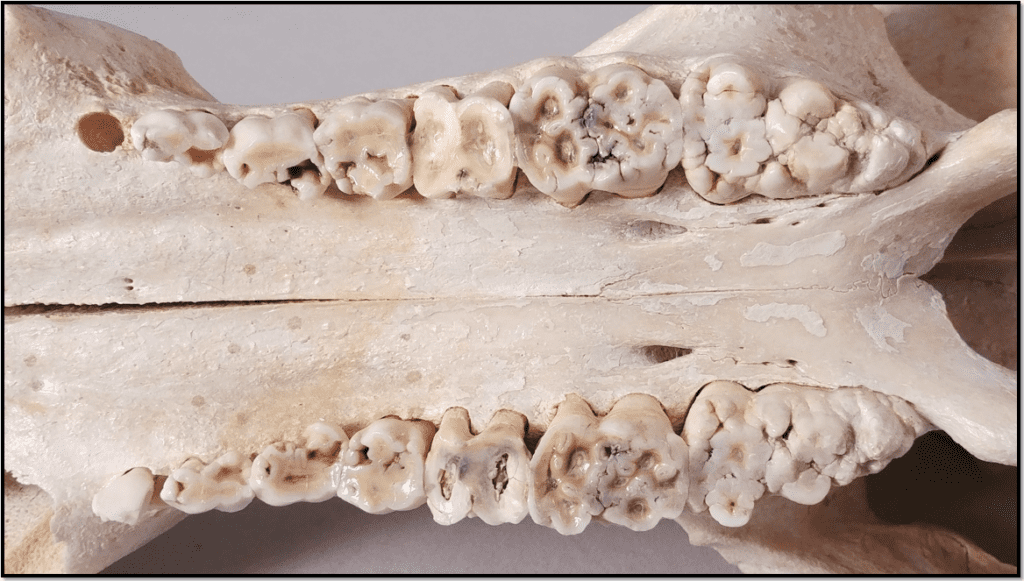

Cattle (Bos taurus) and bison (Bos bison/Bison bison) are very similar morphologically so we won’t attempt to separate the species in this guide. Bison lived in Ohio from the Ice Age until about the year 1800, and cattle were introduced to North America by Europeans. Keep in mind that most finds in Ohio of such teeth are from modern cattle, due to the large number of cattle that have lived in the state for 200+ years. However some bison remains have been found. Cattle and bison also have high-crowned (hypsodont) cheek teeth, although the shape of the tooth is much different than in the horse. Note that the cusps in cattle and bison appear as a series of crescents (selenes) when viewing the chewing surface. This is known as a selenodont crown pattern.

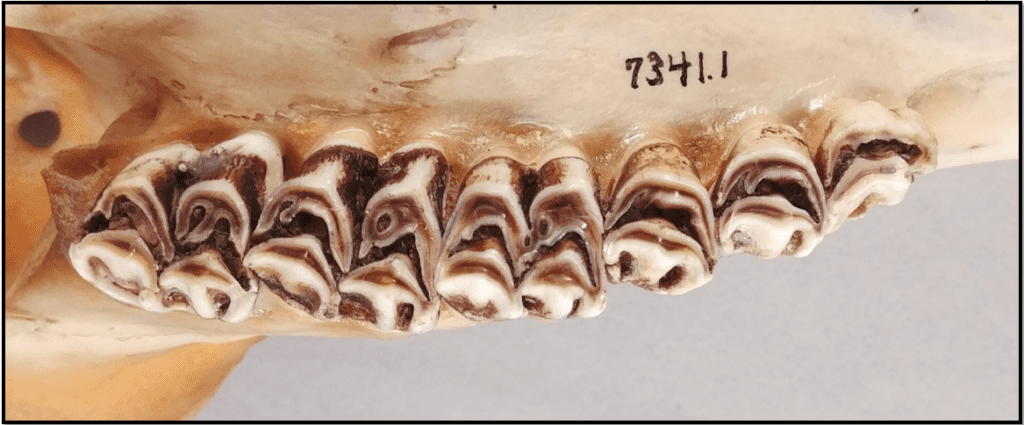

Upper left toothrow of domestic cow; anterior is to the left. This specimen is from a young individual and the last molar (3rd molar) has not erupted yet.

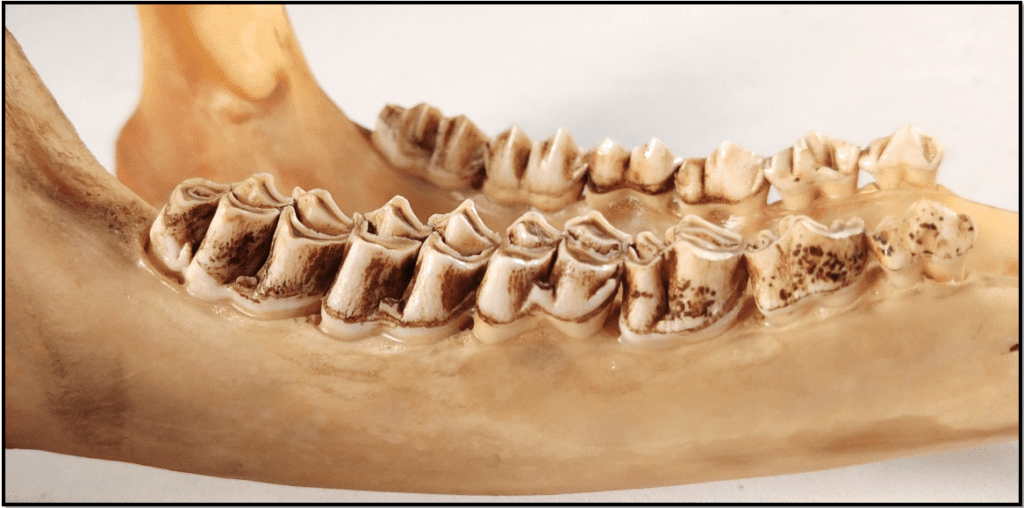

Toothrow of right mandible of domestic cow; anterior is to the right.

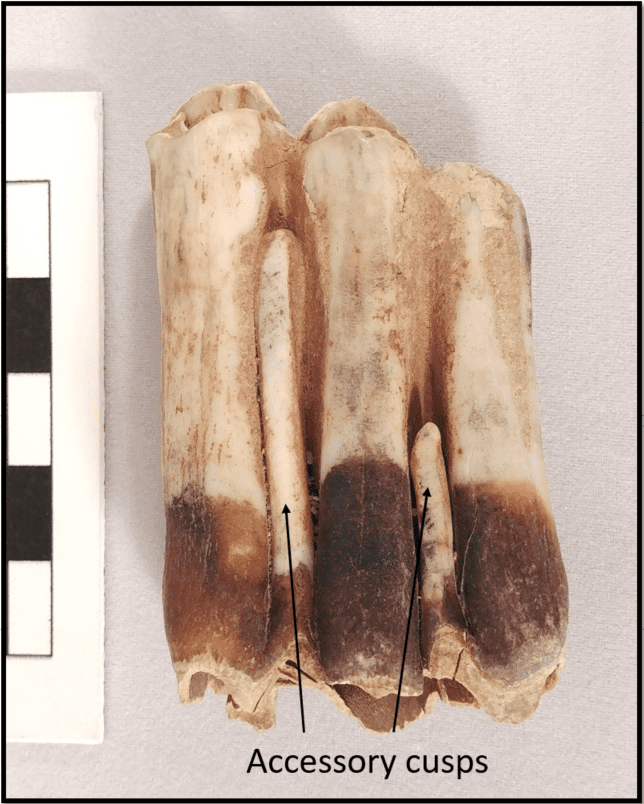

Domestic cow – lower left 3rd molar. Note the high-crown, and the accessory cusps which are visible on some cattle and bison molars. Scale is in centimeters.

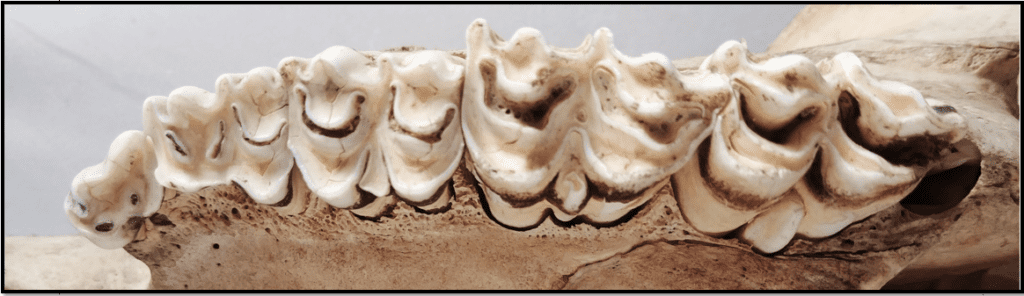

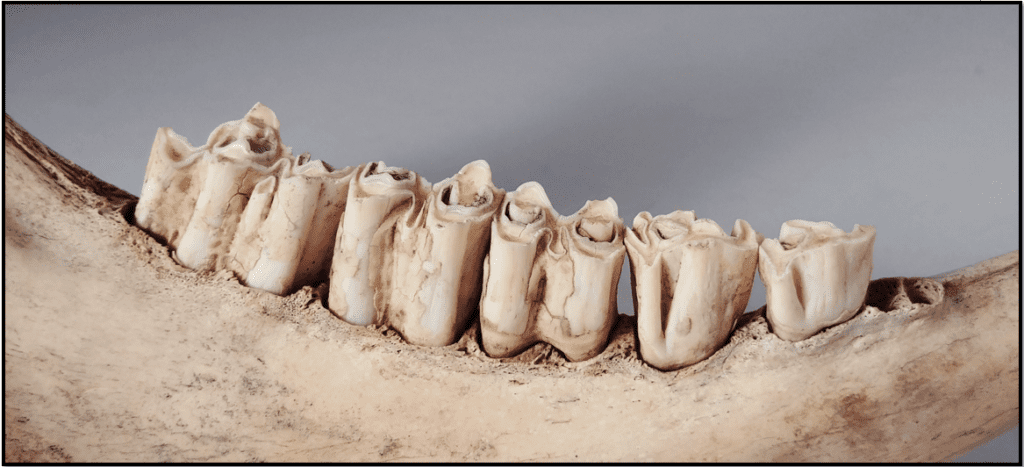

Elk (Cervus canadensis) lived in Ohio from Ice Age times until about 1850, and elk remains are still occasionally found in the state. However you are much more likely to find teeth of White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus), a common species across Ohio. Deer and elk are both in the deer family (Cervidae) and have low-crowned (brachyodont) molars and premolars. This means that the crown is lower and stops at the gumline. We’ll illustrate deer teeth here, but elk teeth would be very similar only larger. Deer and elk also have a selenodont crown pattern as we saw above in cattle and bison. Sometimes very worn teeth of elk and cattle/bison can be difficult to tell apart.

White-tailed Deer – upper left toothrow; anterior is to the right.

White-tailed Deer mandible; anterior is to the right.

Pig or Wild Boar (same species: Sus scrofa) have molars and premolars with low rounded cusps, called bunodont teeth, and are useful for crushing food. Pig teeth are one of the most common types of teeth that we’re asked to identify. Pigs have a complex and very distinctive crown pattern which helps to identify them. Bunodont dentition is most commonly found in omnivores, animals that have a varied diet of many types of food. Bunodont cheekteeth are also found in raccoons, bears, and yes, in humans too!

Upper toothrows of a pig; anterior is to the left. Note that the first left premolar is missing.

Pig – toothrows of the mandible; anterior is to the left.

Upper canine (“tusk”) of a pig. Scale is in centimeters.

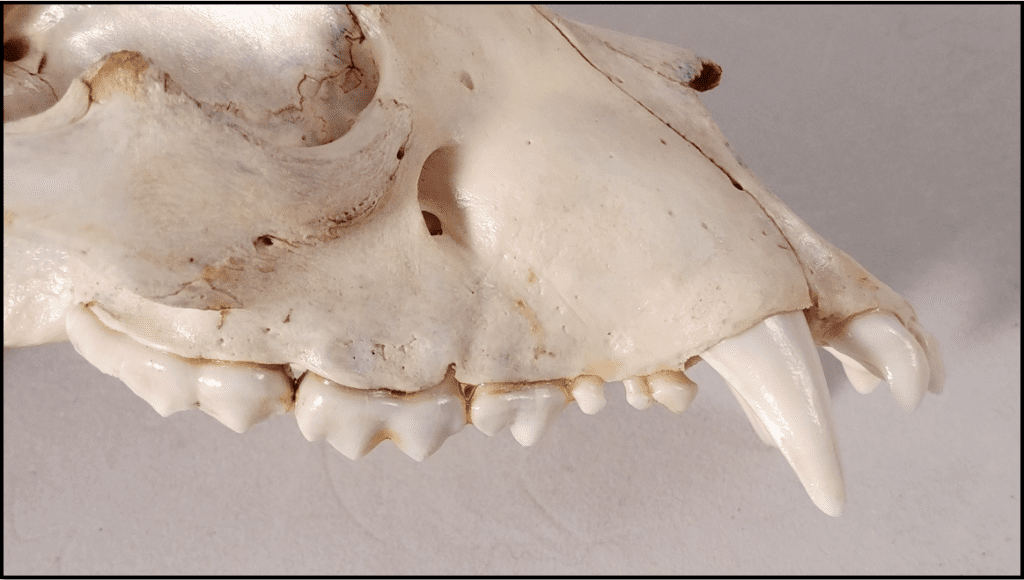

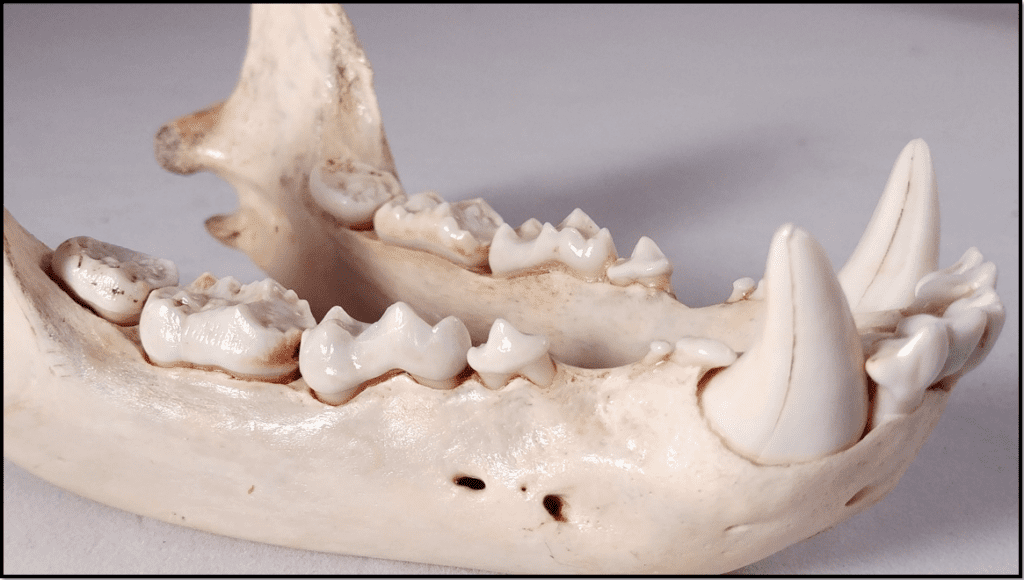

Black bears (Ursus americanus) were common in Ohio from the Ice Age until about 1850, when they were extirpated from the state. However in recent years black bears have been returning to Ohio. As mentioned above, bears also have bunodont cheekteeth with low rounded cusps. They also have large upper and lower canines which are distinctive.

Black Bear – right lateral view of upper toothrow.

Black Bear mandible.

All photos credit Ohio History Connection.

MORE OHIO SPECIES

We couldn’t cover every possible mammal species that might occur in Ohio but this is a good starting place. Here are some species to be aware of, both extirpated and extinct, that we didn’t include but all are much less common than the other species in this blog.

Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos) – skull and teeth similar to black bear but larger; one Pleistocene record from Ohio.

Giant Short-faced Bear (Arctodus simus) – present in Ohio during the late Pleistocene and is often described as the largest land carnivore in Ice Age North America; one Pleistocene record from Ohio.

Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) – lived in Ohio from Ice Age until about 1850.

Dire Wolf (Aenocyon dirus) – teeth similar to the gray wolf, but a little larger. However, the carnassial teeth (enlarged pair of a lower molar and upper premolar for shearing meat) in the dire wolf are much larger. One Pleistocene record from Ohio.

Muskox (Ovibos moschatus) and the extinct Woodland Muskox (Bootherium) – both species were found in Ohio in the Ice Age; teeth would be somewhat similar to cattle or bison.

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) – lived in Ohio in Ice Age and teeth similar to deer or elk.

Stag-moose (Cervalces scottii) – a large Ice Age relative of the modern elk, with teeth similar to elk.

Flat-headed Peccary (Platygonus compressus) – Ice Age pig-like species but its cheekteeth had higher cusps than in pigs, for an omnivorous diet including browsing on coarse vegetation; upper canines are straight and point downward rather than curved like pig/wild boar.

Jefferson’s Ground Sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii) – an unusual Ice Age species with large peg-like cheekteeth.

Giant Beaver (Castoroides ohioensis) – skull and cheekteeth very similar in appearance to the modern beaver but much larger; had very large incisors.

For more information:

Animal Skulls: A Guide to North American Species – by Mark Elbroch, 2006. Stackpole Books.

Mammal Bones and Teeth: An Introductory Guide to Methods of Identification – by Simon Hillson, 2009. Institute of Archaeology Publications, University College London.

A Key to the Skulls of North American Mammals (4th Edition) – by Monte Thies, 2015. Kendall Hunt Publishing.

Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan: https://animaldiversity.org/

Includes lots of skull photos, and a section on mammal teeth: https://animaldiversity.org/collections/mammal_anatomy/tooth_introduction/