Content warning: This post contains brief descriptions of violence.

Did you know that archivists sometimes need to use other archives to research our own collections? Archives are a large network of available information, and sometimes you need multiple parts of the network to make something click.

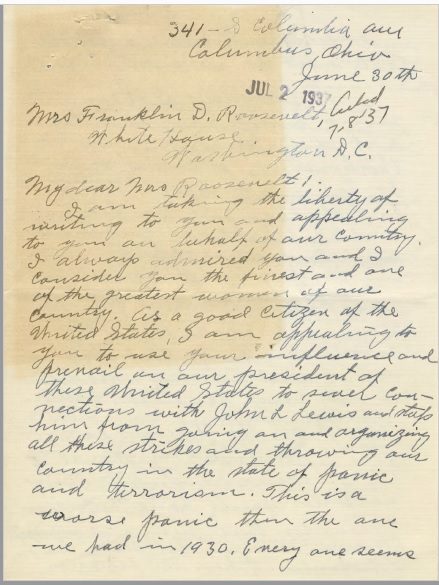

This recently happened with an exciting letter in our collections. The letter is confusing without more context, but it is exciting because of the author- Eleanor Roosevelt. From looking at the letter we can tell that the First Lady was writing to a Mrs. C.J. Penfield in Columbus, Ohio, from the White House. Roosevelt is angry at Penfield for her economic suggestions and does not mince words. But the exact details of what motivated this correspondence are hard to determine.

Lewis and his compatriots believed that organizations like the American Federation of Labor (AFL) needed to begin to include industrial workers in their efforts, rather than the traditional tradesmen they had built their organization upon. At the 1935 AFL convention, Lewis purposefully provoked the leader of the Carpenters Union into a verbal dispute…and then Lewis punched him in this face. With this blow to the face, Lewis also landed the final blow for a united AFL. Like-minded labor activists split from the AFL, and Lewis soon became the first president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

One of the first acts of the CIO was a strike for better wages for steel workers. In March 1937, US Steel agreed to many of their demands, but the smaller steel organizations, together known as “Little Steel” did not concede.

***

As Lewis grew to be the public face of the labor movement, the Penfield family of Columbus, Ohio, quietly benefitted from American labor. Mrs. C.J. Penfield (Nancy), the author of the letter to Eleanor Roosevelt, was the wife of wealthy chain store owner Clare J. Penfield. The Penfields’ stores were likely selling items dependent on the labor of the workers that John L. Lewis was encouraging to strike.

The Penfield family made national news not long before Eleanor Roosevelt made it into the White House. In December, 1931, a nationwide search began for young Virginia Penfield, or the “Ohio Heiress” as one headline in the Akron Beacon Journal deemed her.

Virginia Penfield, 19 at the time, attended the Mary Lyon School in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. In mid-December she left her school, went to Philadelphia, and purchased a train ticket to Columbus. Despite the destination on her ticket, Virginia somehow ended up in Rhode Island, and checked into a hotel under the name “B. Smith.”

Virginia was recognized by a local man who reported her as the heiress everyone had been looking for. Virginia’s father came to retrieve her, telling the Associated Press that Virginia had experienced a breakdown of fatigue from her studies. Virginia claimed not to remember anything after she stopped in a Philadelphia store. Clare Penfield asked the media to let his daughter rest and then said, “I need a vacation too.”

***

On May 26, 1937, after Little Steel had failed to sign any labor agreements, 75,000 workers walked off the job at once. Many of these workers were Ohioans, based at Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company or Republic Steel. Workers created picket lines and in some cases, to avoid their employers hiring non-striking “scabs,” the workers conducted sit-down strikes. During this type of strike, workers still came into the factory, but refused to work.

The Little Steel strikes, which lasted throughout the summer of 1937, often led to fatal violence between police and striking workers. On Memorial Day, in what became known as the Memorial Day Massacre, Chicago Police fired on a group of steelworkers picketing outside Republic Steel, many accompanied by their young children. Ten people died and many others were injured.

Ohio saw the Women’s Day Massacre on June 19, 1937, at the Youngstown Republic Steel plant. For “Women’s Day,” steelworkers’ wives were prepared to work the picket line. Police Captain Charley Richmond, who was in charge of the police force at the picket that day, did not agree that women should be on a picket line. He was enraged when union organizers refused to remove the women at the plant. He began to aim misogynistic comments at the women, and a verbal clash ensued. Growing angrier, Richmond threw tear gas grenades at the picketing crowd of women and children.

Violence ensued, and eventually the police opened fire on the crowd. Union organizers ran emergency extraction operations all throughout the day. One organizer later said, “When I got there I thought the Great War had started over again. Gas was flying all over the place and shots flying and flares going up and it was the first time I had ever seen anything like it in my life…” By the end of the day multiple people were dead.

***

It was during this summer of picketing and violence that Mrs. Penfield wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt, demanding an end to the labor movement. She approached Roosevelt as one wife to another, asking Eleanor to exert power over her husband, the President. Penfield wanted President Roosevelt to, “sever connections with John Lewis and stop him from going on and organizing all these strikes and throwing our country in the state of panic and terrorism.”

Penfield often called out Lewis specifically in her letter. Although Lewis himself was not involved with most of the strikes against Little Steel, he had been made both a hero and a villain of the labor movement, depending on your opinion of the situation. Penfield worried that Roosevelt would “sell our country out to John Lewis for thirty pieces of silver.”

Penfield was also certain to note that in Columbus, “we can’t get help of any kind for housework or anything else. Everyone…goes on relief and the government is making a lot of lazy people…”

Roosevelt wrote back to Penfield in July, as Ohio sent National Guard troops into its cities to break up the Little Steel strike. Her letter, which is now a part of our collections, was filled with sharply worded critiques. Of Penfield’s fear of a national panic, Roosevelt wrote, “Your particular group of people may feel that way but I assure you that the country is not in the condition that it was in 1930 or 1933.”

Roosevelt went on to explain to Penfield that many Americans on relief had turned down available jobs, because the wages were not high enough to support their families. Roosevelt stated, in a sentence dripping with disdain, “I wonder if the reason you could not get household work done is because you offer inadequate wages?”

Eleanor Roosevelt finished her letter to Mrs. Penfield by saying, “I am afraid the women with whom you come in contact are more interested in their own comfort than they are in the real good of the country. Very sincerely yours, Eleanor Roosevelt.”

***

By the end of the summer of 1937, Little Steel had won. Disappointed with President Roosevelt’s lack of support for the strike, John L. Lewis worked against his reelection the following year. When Roosevelt was reelected, Lewis took it as a mandate and stepped back from the limelight. For a few years, the conversation about Little Steel subsided.

Finally, as WWII took hold of the nation in the early 1940s, Little Steel was forced to acquiesce to the unions. In need of workers to support the war effort, they had very little choice but to finally recognize the rights of the workers that were central to the nation’s success. Little is known about what happened to Mrs. Nancy Penfield after her letter. She passed away in 1960 and is buried in Columbus, Ohio. Eleanor Roosevelt continued her role as First Lady until 1945, after which she began working with the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. She passed away in 1962. John L. Lewis threw himself into his work at the UMWA. He passed away in 1969. In 1947, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, limiting the reach of the labor unions that had fought such hard won victories in the earlier part of the century.

***

Interested in learning more? Below are some of the resources used to write this blog post:

Encyclopaedia Britannica

AFL-CIO

Case Western Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

Zinn Education Project

Truthout

Brownsville herald

Evening star (Washington D.C.)

Indianapolis times