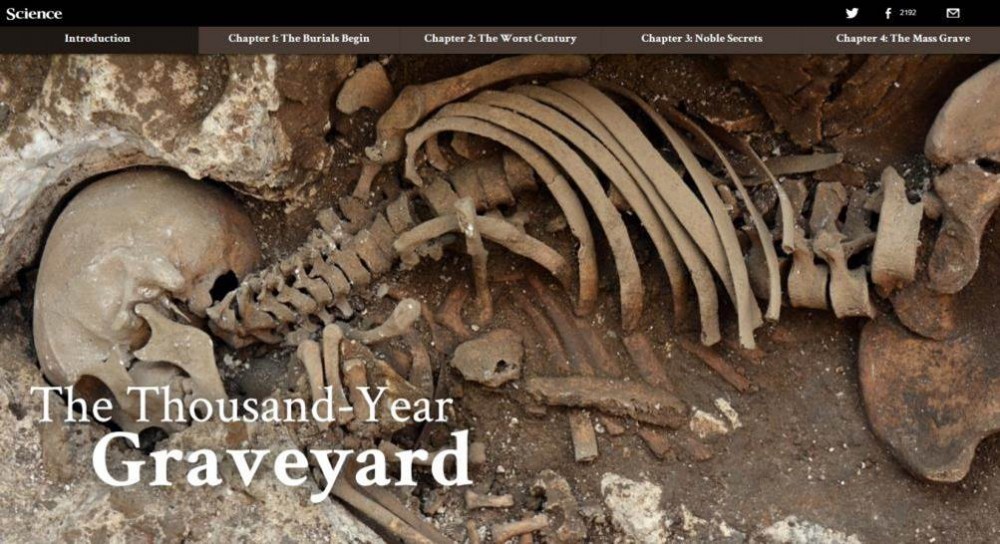

This week, in the journal Science, there is a review of a remarkable investigation taking place in the Bodia Pozzeveri churchyard in Altopascio, Italy. Clark Spencer Larsen, a biological anthropologist at the Ohio State University, is the project’s co-leader. The team is studying the remains of people that were buried there from the 11th through the 19th centuries. Along with the traditional forensic studies, the scientists are using 3D scanning of the bones, sampling of chemical isotopes from teeth, and even analyses of ancient DNA. George Armelagos, a professor of anthropology at Emory University, is quoted in the article as saying that this project is “going to be the poster child for future work in bioarchaeology.”

This week, in the journal Science, there is a review of a remarkable investigation taking place in the Bodia Pozzeveri churchyard in Altopascio, Italy. Clark Spencer Larsen, a biological anthropologist at the Ohio State University, is the project’s co-leader. The team is studying the remains of people that were buried there from the 11th through the 19th centuries. Along with the traditional forensic studies, the scientists are using 3D scanning of the bones, sampling of chemical isotopes from teeth, and even analyses of ancient DNA. George Armelagos, a professor of anthropology at Emory University, is quoted in the article as saying that this project is “going to be the poster child for future work in bioarchaeology.”

In an accompanying editorial, Armelagos laments that projects such as this, which have the promise to shed much-needed light on “the evolutionary epidemiology” of ancient diseases, are becoming increasingly difficult if not impossible to undertake in the United States due to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Armelagos acknowledges that NAGPRA was “conceived with good intentions” and in many cases has “stimulated constructive interactions by all stakeholders,” but the legislation has hampered potential research that could shed much-needed light on, for example, how European introduced diseases have ravaged Native American populations. Such research has the potential to aid medical science and agencies charged with the management of future pandemics. Armelagos concludes his commentary with a call for the scientific community to “increase its engagement with the public, policy-makers, and tribal communities in ways that clearly explain how access to human remains, in an ethical and respectful manner, holds great potential for understanding the diseases that affect their own health.” I agree with Armelagos. It is absolutely essential for archaeologists to reach out to all of these groups, but particularly to American Indian tribal communities many of whom don’t trust archaeologists to be ethical and respectful in their treatment of human remains. And why should they? The history of archaeology and biological anthropology includes too many examples of sometimes egregiously unethical and disrespectful practices.

Indeed, the original intent of NAGPRA — its reason for being — was to begin to redress this history by allowing lineal descendants or culturally affiliated tribes to reclaim human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony from museums. In consultations with Native American tribes on such issues, I have been told that no archaeologist had ever before attempted to explain what the study of human remains might contribute to a knowledge of their history or to the potential future health of their people. I was astonished and embarrassed to realize that, in the absence of any outreach or public education initiatives, archaeology’s interest in human remains was a troubling mystery to many tribal members. Is it any wonder then that, according to Joe Watkins, many American Indians equate archaeologists with pot hunters, grave looters, or worse? Armelagos is right to call for broader engagement with the public, policy-makers, and especially tribal communities. NAGPRA doesn’t have to mean an end to all scientific research on human remains if tribes decide that such research would be of value to them. Archaeologists and biological anthropologists must make the case that studies of human remains have the potential to teach us much of value about the lives of our ancestors. What Larsen and his team are learning about the people buried in the Bodia Pozzeveri churchyard hints at what we could be learning from studies of the remains of ancient American Indians.

Brad Lepper

For further reading:

Armelagos, George 2013 Reading the bones. Science 342:1291. Watkins, Joe 2000 Indigenous archaeology: American Indian values and scientific practice. Alta Mira Press, Walnut Creek, California.