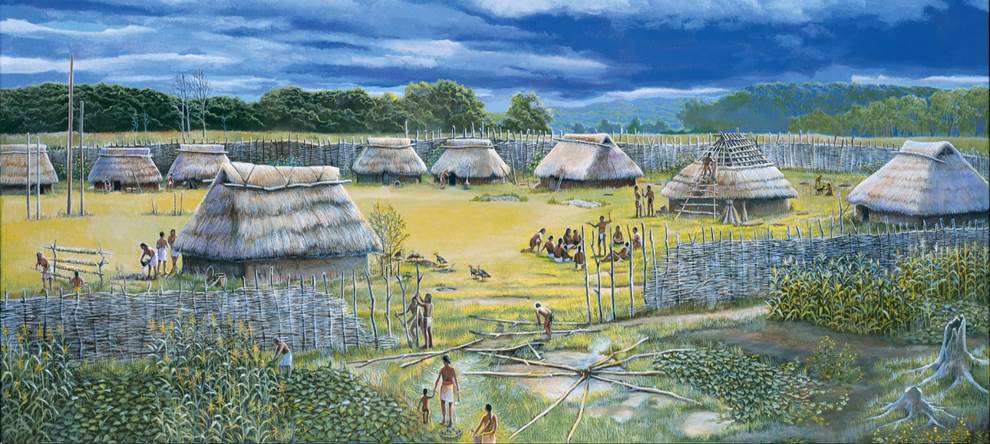

Late Prehistoric period village in Ohio. Ancient Ohio Art Series, Susan Walton, artist

The transition from the Late Woodland (A.D. 400-1050) to the Mississippian (A.D. 1050-1500) period is one of the most significant cultural transformations in eastern North American prehistory. Jennifer Raff, a research fellow in Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin and co-author of

a new study of ancient DNA spanning this transition, notes that it involved changes to social and political structure, the adoption of intensive maize agriculture, changes to mortuary practices and the development of new art, technologies and religious practices.” Raff and a team of other researchers decided to compare DNA recovered from Late Woodland and Mississippian individuals who lived at the same site in order to see if the cultural changes were associated with the movement of people from outside the area or if local folks adopted the changes more or less on their own. Raff says, “these cultural changes first appeared at the nearby site of Cahokia, just east of present-day St. Louis, so we wanted to know if migration from there had brought the changes to the Lower Illinois River Valley. The results, presented in

a forthcoming issue of the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, reveal that these rapid cultural changes resulted from the adoption of new cultural practices through existing social networks rather than from a migration of new people into the region. Raff’s co-authors include Deborah Bolnick, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology and the Population Research Center, Austin Reynolds, a graduate student in the Department of Integrative Biology at UT, Della Cook, professor of anthropology at Indiana University Bloomington, and Frederika Kaestle, associate professor of anthropology at Indiana University Bloomington. The team recovered segments of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from 39 individuals (17 Late Woodland, 22 Mississippian) who had been interred in the Schild cemetery in western Illinois. They then compared these mtDNA lineages to ancient lineages identified at other sites in the region. Reynolds concludes that this study provides valuable insights into how sites peripheral to the largest Mississippian settlements incorporated new cultural practices during this transitional period. The local people clearly adopted Mississippian practices, suggesting that cultural shifts in the archaeological record are not always caused by replacement of the previous inhabitants of a region. These results have important implications for our understanding of this transformational period in Ohio, but Bolnick cautions that more research is needed to determine whether the findings in the Lower Illinois River Valley are representative of the process of culture change across eastern North America during the Late Woodland-Mississippian transition, or whether this change was triggered by acculturation in some regions and migration in others. It’s also important to keep in mind that mtDNA doesn’t tell the whole story. It is passed from mother to child and allows researchers to trace maternal relationships and female migration. In the future, Reynolds says, it will be important to obtain information from other regions of the genome. For example, studying the paternally inherited Y chromosome, which is passed down from father to son, would allow us to test for male migration during this cultural transition and further refine our models of demographic change in the region. Previous work done in our lab has suggested that in the past, the movement of males and females may have been very different in the eastern United States. This post is based on

a news article from the University of Texas at Austin’s webpage as well as

the abstract of the AJPA paper.