I recently received a web-posting with links to an article about museums and taxidermy specimens. The author, Rachel Polquin muses in her article about the philosophical meaning of old mounted animals in museums and cites an example of one museum in Britain where they destroyed all the old, musty, taxidermy specimens a few decades ago. She has recently curated an exhibit of old taxidermy mounts at the Museum of Vancouver. The article is an interesting read.

One thing she says in her article isWhile I never advocate the making of new taxidermy, I believe that taxidermied animals, as old and musty as they might become, can be reinterpreted as not just something to look at, but something to think with.

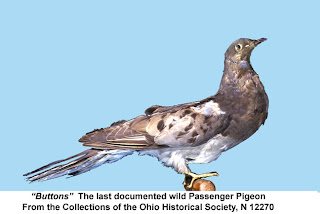

Yes! Taxidermied specimens can and should become something to think about. The Ohio Historical Society has on exhibit Buttons the last documented wild Passenger Pigeon, which was shot in Pike County, Ohio in 1900. We are approaching the 100th anniversary of the death of Martha the last captive Passenger Pigeon and the last of its species, which died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. That bird was mounted as is housed by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Viewing either of those mounted Passenger Pigeons should get all of us thinking about how we have impacted species in the past and the present. What can we do now to keep common species from becoming endangered and endangered species to become extinct?

However, I find the first part of Polquins statement incongruous with her other sentiments. If old taxidermy mounts have value why not create the same value for the future by preserving specimens currently? Certainly I can understand not promoting the shooting of a California Condor or a Whooping Crane to make an exhibit but if one dies from other causes, why not preserve it for the future when perhaps it could be as important to society as our Passenger Pigeons are to us today? In our museum we almost never go out and trap and shoot animals to make exhibit mounts but they are often readily available as road kills or window kills and are to us a valuable resource.

What about taxidermy mounts of more common species? It is certainly possible that species common today could become endangered tomorrow. Look at the sudden and catastrophic demise of ash trees since the accidental introduction of the Emerald Ash Borer into the Detroit-Toledo area in 2002! Just a few years ago I planted several ashes since they were hardy and abundant, native and very attractive. My ash trees are now threatened, and many millions have already died.

House Sparrows (aka English Sparrows) have become a significant nuisance species in North American since their purposeful introduction from Europe as early as 1850. An estimated 150 million House Sparrows in North American compete with native species, create messy nests around our homes, tear up home ventilation and insulation and even spread disease. From the 1950s to the 1970s in the UK their native populations were at between 9.5 and 12 million birds. In the last 25 years, their populations have crashed by 62% — and they are now a red listed species of high conservation concern in the UK. What has caused this? Will they eventually become extinct in their native habitat? Will mounted specimens become invaluable? It is hard to know at this point, but it shows us that we often cannot predict drastic changes in common wildlife species.

But even if the animals are common, and will remain common, do not taxidermied mounts offer a great educational value? Sure, almost anyone would prefer to watch the live animal up close and personal, vibrant and alive with all their wonderful behavior. But even with zoos and parks, sometimes we cannot make the same extreme close examination in the wild that we can of a mounted specimen. Photographs are also great and offer many advantages, but they dont carry the same impact as being inches away from a six-foot-tall Bison. Our museums education staff have often watched children and adults totally engaged in looking at mounted animals. A few people may be creeped out by the mounts, but many, many more are fascinated by them. Zoo animals dont stand still as readily for close inspection. I know of one scout group who spent the greatest part of their visit studying our mounted animals. High school students study them to help learn how to identify the species, a skill that can be fun but can also serve them in the Envirothon competitions. (Learn more about Ohios Envirothron at http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/tabid/8652/Default.aspx ) The up close look shares not only the shape and color of the animal, but the size as well. Proportions of legs, wings, muscle groups, etc. also help us understand adaptations of the animals for their environment.

Then there is also the scientific value of taxidermied specimens. Measurements can be made, which added with many other specimens, can lead to an understanding of size ranges or color changes as they vary with geographic setting. Traces of pesticides or pollutants used many years ago can be detected in the specimen and tell us something of their life history and how it was impacted. DNA can be taken from a few hairs, feathers, or skin fragments where the specimen was sewn together, helping us understand the genetics of changing populations over the years. Many, many research projects have used taxidermied specimens, as well as their less aesthetic cousins, the study skin.

So, I would definitely advocate the making of new taxidermy. What are your thoughts on this subject?

Robert C. Glotzhober

Senior Curator, Natural History