Ohio’s Hopewell culture is best known for the series of gigantic mounds and earthen enclosures, which these ancient American Indians built between about AD 1 and 400. The Ohio History Connection is working with Hopewell Culture National Historical Park and other partners to get eight of the best surviving examples of this indigenous architecture inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

The sites that we hope to include in the nomination already are recognized as National Historic Landmarks and include the Fort Ancient Earthworks in Warren County, the Great Circle and Octagon Earthworks in Licking County, and Mound City, Hopeton Earthworks, Hopewell Mound Group, High Bank Works, and Seip Earthworks in Ross County. These amazing sites are being nominated for their grandeur; and for what they can tell us about the depth of knowledge of geometry and astronomy that are embedded in their designs. They also are remarkable because the ancient American Indians who built them did not live in cities ruled by an authoritarian leader who could command people to undertake these massive public works. Instead, they lived in small, dispersed communities and they would periodically gather together in large numbers at these ceremonial centers.

The earthworks, however, tell only part of the story. If we want to understand what actually took place at these amazing sites and learn about the people who built the earthworks and worshipped there, then we need to study the things they left behind.

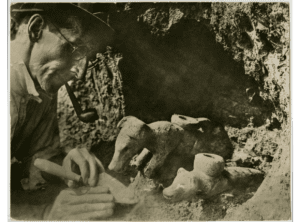

Henry Shetrone, an archaeologist with the Ohio History Connection, excavated Seip Mound in the late 1920s. Among the artifacts he uncovered was an extraordinary pipe carved in the shape of a dog chewing on a human head. We know it’s a domesticated dog and not a wolf, because of its drooping ears and curly tail. These are characteristic of domesticated dogs and not wolves.

People domesticated dogs between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago; and the first people to come to America, around 16,000 years ago, brought their dogs with them. The dogs may have helped hunters track and drive game animals and also may have pulled burdens on a travois, which was a kind of simple sledge. Native peoples also ate dogs when other food was scarce or as part of ceremonial feasts.

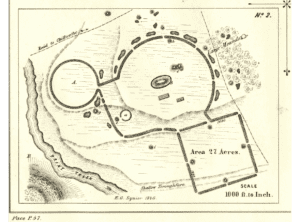

Seip Mound is located within a large circular earthen enclosure, which is connected to both a smaller circle and a square. The Seip Earthworks now are part of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park.

The dog effigy pipe is made from steatite, or soapstone. It is eight inches (204 mm) long, much larger than typical Hopewell platform pipes. Based on the size, it appears to have been intended for multiple users perhaps in a communal ceremony.

Although buried in an Ohio Hopewell mound, the style of the pipe along with the material from which it was made indicate that it was made by artisans of the Copena culture who lived in northern Alabama. People from the Copena region may have brought this set of five pipes to Ohio as gifts or offerings. Alternatively, someone from southern Ohio may have travelled to the Tennessee Valley and brought back these unusual pipes.

The ancient American Indian ancestors buried this pipe along with four other similar effigy pipes in Seip Mound as some kind of special offering. It was not a funerary offering for there were no human remains associated with them. One of the other pipes was also a dog effigy. Originally, it too may have been chewing on a human head, though whatever it might have been holding between in its paws had broken off sometime in antiquity.

A dog chewing on a human head might be interpreted as a grisly reminder of what happens to a defeated enemy. Instead of being respectfully buried, their remains are eaten by dogs. There is, however, no evidence for warfare during this period. There are no known human remains from Hopewell sites that bear wounds of war and there are no artistic depictions of warriors. Therefore, this dog and human head likely represent a traditional story or possibly a folktale, like an Aesop’s fable, rather than a depiction of the aftermath of an actual battle. This interpretation is supported by the possibility that the other dog effigy pipe also appears to be telling the same story. Given that the pipes likely served a religious purpose, the story is likely to have had a religious significance. The story associated with this dog and a human head is likely to have been as familiar to the Hopewell and Copena groups as the story behind an image of a naked woman holding an apple would be to someone from the Judeo-Christian tradition.

The dog effigy and the other large effigy pipes from Seip Mound currently are displayed in the ‘Following in Ancient Footsteps’ exhibit at the Ohio History Center.

***

For further information about the Hopewell culture and Seip Mound

Lepper, Bradley T.

2005 Ohio Archaeology: an illustrated chronicle of Ohio’s ancient American Indian cultures. Orange Frazer Press, Wilmington, Ohio.

Shetrone, Henry C. and Emerson Greenman

1931 Explorations of the Seip Group of Prehistoric Earthworks. Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 40:343-509; https://resources.ohiohistory.org/ohj/browse/displaypages.php?display[]=0040&display[]=343&display[]=509

Virtual First Ohioans: Seip Mound: http://ohsweb.ohiohistory.org/gallery2/main.php?g2_itemId=586

For more information about the work to nominate the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks to the UNESCO World Heritage List