Ohio Artist Archibald Willard and the “Spirit of ’76”

Learn more about Archibald Willard, the Ohio artist who painted "Spirit of '76" to celebrate our nation's 100th birthday.

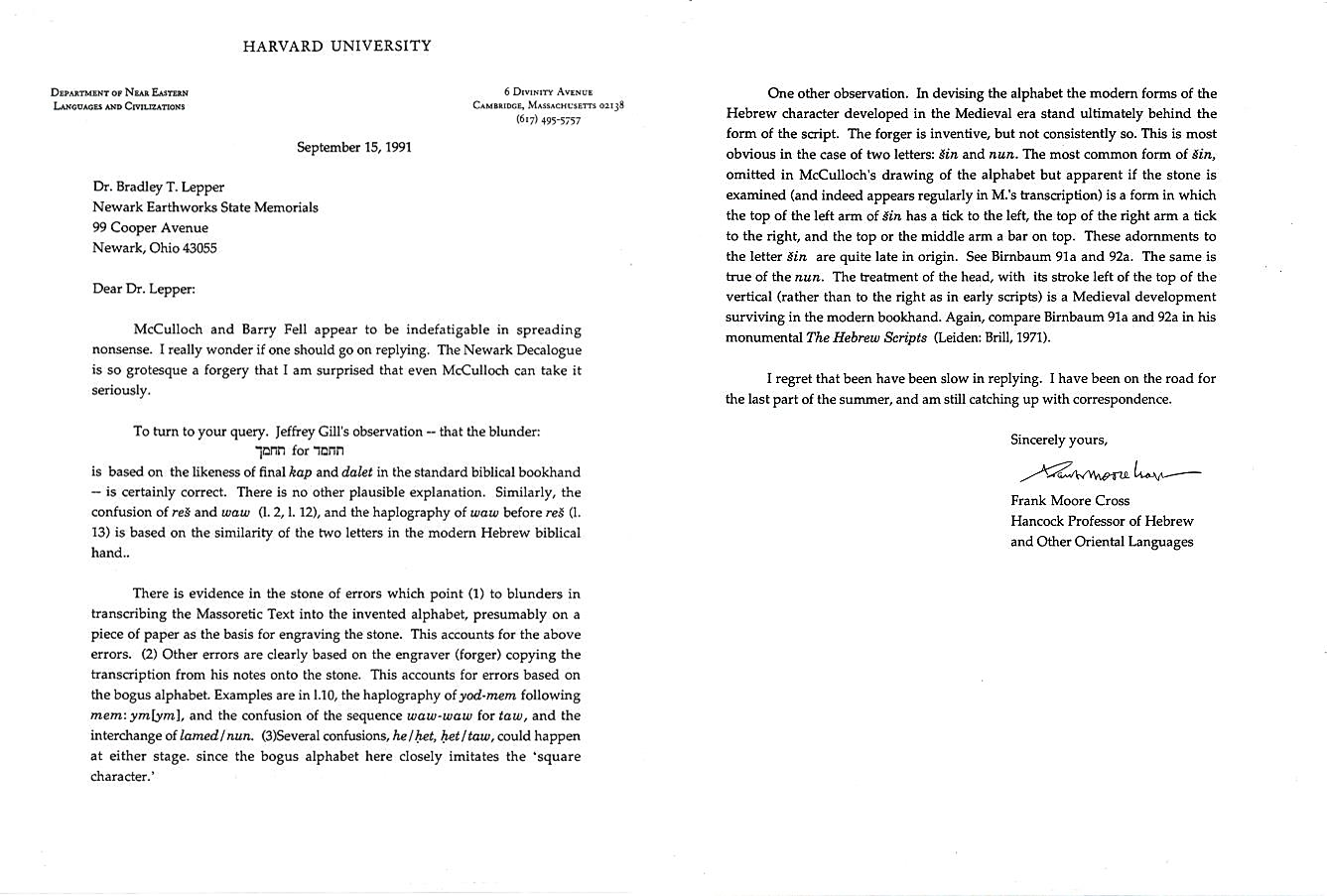

Back in the summer of 1991, Jeff Gill, an avocational archaeologist and all around polymath, and I were just beginning to make a serious effort to figure out what the Newark Holy Stones were all about. Jeff, a Disciples of Christ minister, had studied Hebrew at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis. In looking over an analysis of the Decalogue Stone inscription published by Ohio State University professor of economics Huston McCulloch, he noticed a recurring pattern of errors that appeared to indicate that the inscription must have been based on modern (19th century) Hebrew. The late Frank Moore Cross, then an emeritus professor at Harvard University’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, was not only one of the world’s foremost scholars of ancient Hebrew, but he also had shown a willingness to work with North American archaeologists in the study of dubious artifacts. We therefore decided to write Cross a letter to see if he agreed with Jeff’s conclusions. Here’s how we summarized Jeff’s argument for Cross: “In the section of the inscription corresponding to Exodus 20.16, the verb ‘to covet,’ (DMH) appears twice in the Qal imperfect (DMHT). However, the first use of this verb on the stone is given as (KMHT), a ‘kaph’ replacing the expected ‘daleth’ Whereas in Hebrew a terminal ‘kaph’ might well be mistaken for a ‘daleth,’ in the ‘Decalogue alphabet’ there is no such similarity It would seem that only someone consulting a [modern] Hebrew original and transposing into this ‘cipher’ could have placed a ‘kaph’ at this point, especially since a) the second usage of the same verb immediately following is correctly given as (DMHT), and b) every other ‘sic’ is either a complete omission, an insertion between correct letters, or a mistaken transcription of letters that are similar within the ‘Decalogue alphabet.'” Much to Jeff’s gratification, Cross responded that this explanation “is certainly correct”:  Between Gill and Cross’s demonstration that the Decalogue Stone was a forgery and my own discovery of the probable source of its design, any serious debate over its authenticity was over. Since then, Jeff and I have been focused on the fascinating question of just why someone in 1860 would go to all the trouble and risk of creating such a forgery. We have summarized our ideas about that in a couple of papers and blog posts, but every time we plumb the depths of a previously unexplored archive the story becomes even more complicated than we thought.

Between Gill and Cross’s demonstration that the Decalogue Stone was a forgery and my own discovery of the probable source of its design, any serious debate over its authenticity was over. Since then, Jeff and I have been focused on the fascinating question of just why someone in 1860 would go to all the trouble and risk of creating such a forgery. We have summarized our ideas about that in a couple of papers and blog posts, but every time we plumb the depths of a previously unexplored archive the story becomes even more complicated than we thought.

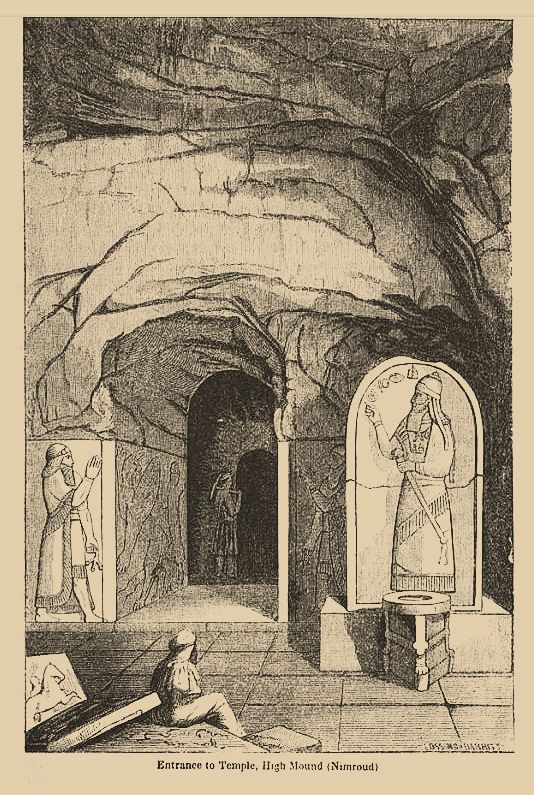

Figure from Layard’s 1853 book Discoveries among the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. Note the similarity between the monument on the right and the form of the Decalogue Stone.

Eventually we’re going to have to write that book we keep talking about to tell the whole story of this scientific forgery that appears to have had a purpose entirely consistent with the name that was applied to it in jest the Newark Holy Stones.

Brad Lepper

FOR FURTHER READING Lepper, Bradley T. 1991 Holy Stones of Newark, Ohio, not so holy after all. Skeptical Inquirer 15(2):117?119. 1992 Just how holy are the Newark Holy Stones? In Vanishing Heritage, edited by P. E. Hooge and B. T. Lepper, pp. 58?64. Licking County Archaeology and Landmarks Society, Newark. 1999 Newarks Holy Stones: the resurrection of a controversy. In Newark Holy Stones: Context for Controversy, edited by P. Malenke, pp. 15-21.Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum, Coshocton, Ohio. Lepper, Bradley T., Kenneth L. Feder, Terry A. Barnhart, and Deborah A. Bolnick 2011 Civilizations lost and found: fabricating history. Part Two: false messages in stone. Skeptical Inquirer 35(6):48-54. Lepper, Bradley T. and Jeff B. Gill 2000 The Newark Holy Stones. Timeline 17(3):16-25. 2008 The Newark Holy Stones: the social context of an enduring scientific forgery. Current Research in Ohio Archaeology 2008, Ohio Archaeological Council