Flint Ridge flint bladelets and cores from the Dodson Village site a flintknapping workshop near Flint Ridge

In the current issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science, archaeologists Marvin Kay and Robert Mainfort, Jr. consider how Hopewell bladelets were used at Pinson Mounds in Tennessee both as tools and social symbols. In my December column for the Columbus Dispatch, I summarize their results and discuss what it all means for our understanding of the Hopewell culture.

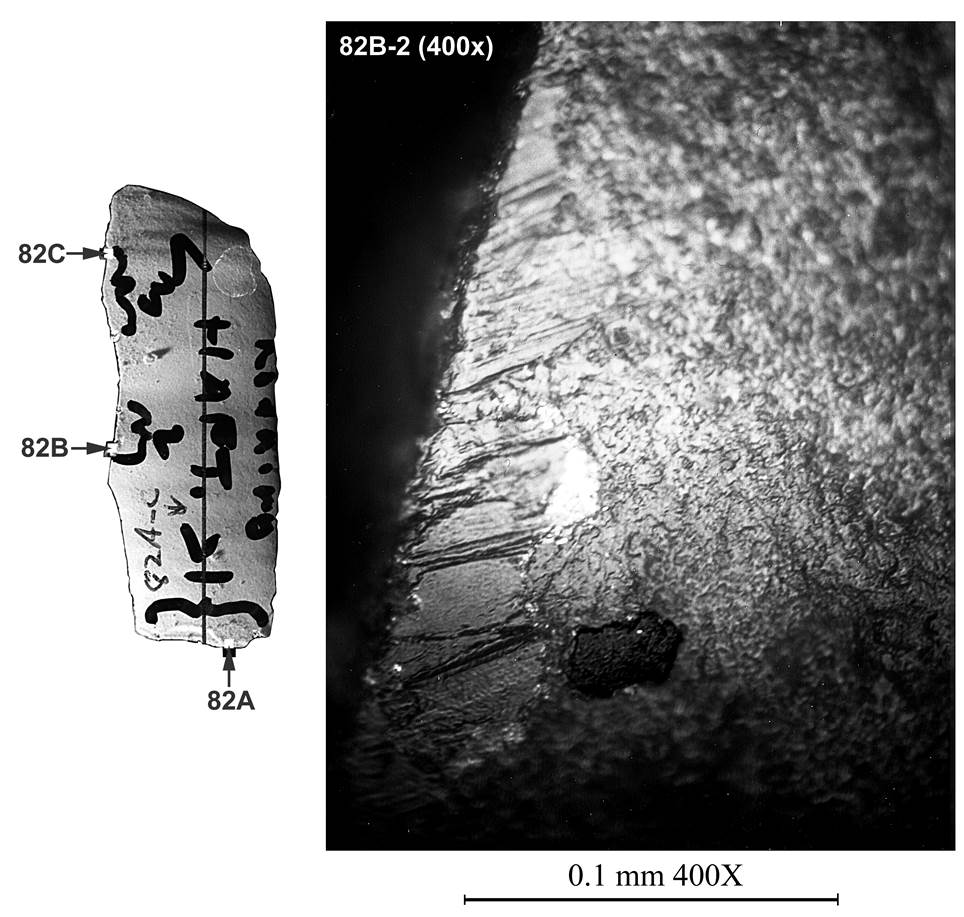

This bladelet from Pinson Mounds was used as a gouging burin (area marked as 82A on the image). It also exhibits wear from being hafted in a handle (areas marked as 82A and 82C). The tool was used until dull on a hard material, such as bone or antler. Image courtesy of Marvin Kay and Robert Mainfort

Kay and Mainfort demonstrate that the Pinson Mound bladelets were remarkably versatile tools. Forty-two had been used as burins, 12 as scrapers, 11 as knives, and seven as gravers. The majority of Pinson bladelets were used to make a range of manufactured goods mostly of wood, bone, antler or similarly hard substances. This largely corroborates what other investigators have found from studies of bladelets at Ohio Hopewell sites. Ohio State University archaeologist Richard Yerkes found that bladelets were used for an even greater variety of tasks, including cutting hide or meat, scraping hides, working bone or antler, wood working, cutting plants, and incising stone. At the LIC-79 sites, located near the Newark Earthworks, meat and hide cutting was the principal activity whereas at the Marietta Earthworks, bone and antler working predominated.

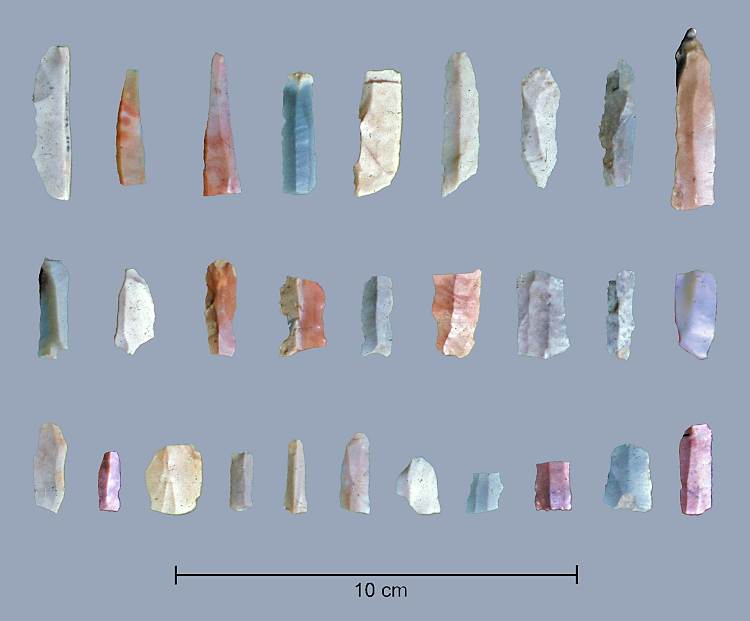

Bladelets made from Flint Ridge flint recovered from Pinson Mounds. Image courtesy of Robert Mainfort

Kay and Mainfort identify the core-and-bladelet technology of the Middle Woodland period as a quintessential symbol of the Hopewell Interaction Sphere. As part of that Interaction Sphere, relatively small but significant quantities of Ohio’s Flint Ridge flint circulated throughout the Hopewell world. Of the 128 bladelets studied by Kay and Mainfort, 33 or about 25% were determined to have been made from Flint Ridge flint. And another 20 were listed as possibly Flint Ridge flint. The predominant stone used for bladelets at Pinson was the more or less locally available Fort Payne chert. As might be expected, the Ohio sites studied by Yerkes had much greater proportions of Flint Ridge flint bladelets. At the LIC-79 sites, for example, 48 percent were made from Flint Ridge flint, 46 percent from Wyandotte chert, sometimes referred to as Indiana hornstone, and two percent from Knife River flint, which was quarried in western North Dakota. Kay and Mainfort write that even though prismatic blade technology was efficient, flexible, and therefore eminently useful, it nevertheless, actually ceased to exist when the Hopewell culture climax ended and had to be reinvented centuries later during the Middle Mississippian period. The use of Flint Ridge flint also declined precipitously at the end of the Hopewell era. To my knowledge, there was no similar drop in the use of Wyandotte chert or Fort Payne chert at this time. What was so special about Flint Ridge flint that regardless of its high quality and striking visual appearance it would be virtually abandoned as a source of tool-making material by post-Hopewell societies?

I’ve directed two extensive excavations up on Flint Ridge and two things seem abundantly clear. First, the Hopewell people quarried Flint Ridge flint on an industrial scale digging hundreds of quarry pits across the Ridge. Second, much of the flint they quarried was turned into bladelets and the cores from which more bladelets could be produced. The quantity of these artifacts manufactured at Flint Ridge and nearby workshop sites was far greater than would have been needed to meet the needs of local folks. I think those artifacts were being made to distribute from Ohio’s major earthwork centers as souvenirs or pilgrims tokens rather than as commodities in a trade network. Kay and Mainfort argue that bladelets were as much a social symbol as they were a handy multipurpose tool. I fully agree and would add that bladelets made from Flint Ridge flint made them even more potent symbols. A Hopewell congregant at Pinson Mounds who possessed a bladelet made from Flint Ridge flint would have been recognized as someone who had made the great hadj to Newark or Chillicothe and might therefore be entitled to a place of special honor at ceremonial feasts.

This may be why the collapse of the Hopewell culture resulted in the abandonment of its signature bladelet technology and the virtual proscription of the use of the extravagantly distinctive Flint Ridge flint. When people reject a belief system that formerly gave meaning to their lives, it would make sense that they would also reject the material symbols most powerfully associated with that belief system. The reasons for the Hopewell collapse, like the reasons for its explosive rise, have yet to be worked out to anyone’s satisfaction. The work of Kay and Mainfort, however, suggests that important clues to an eventual answer may be found along the edges of bladelets.

Brad Lepper

For further reading

Kay, Marvin and Robert C. Mainfort, Jr. 2014 Functional analysis of prismatic blades and bladelets from Pinson Mounds, Tennessee. Journal of Archaeological Science 50:63-83.

Millls, William C. 1921 Flint Ridge. Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society Publications Volume 30, pages 91-161.

Lepper, Bradley T. and Richard W. Yerkes 1997 Hopewellian occupations at the northern periphery of the Newark Earthworks: the Newark expressway sites revisited. In Ohio Hopewell Community Organization, edited by W. S. Dancey and P. J. Pacheco, pp. 175-205. Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio.

Lepper, Bradley T., Richard W. Yerkes, and William H. Pickard 2001 Prehistoric flint procurement strategies at Flint Ridge, Licking County, Ohio. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 26:53-78.

Yerkes, Richard W. 1994 A consideration of the function of Ohio Hopewell bladelets. Lithic Technology 19 (2): 109-127.