Summer in Ohio has arrived once again, and that means it’s Caterpillar Season!

Caterpillars are arguably the most accessible kind of animal wildlife. They aren’t particularly fast moving, are easy to observe up close, they possess a variety of colors and textures, and most caterpillars (in North America, anyway) are harmless and can be safely handled. Those with stinging hairs or spines can be admired from a twig or leaf without touching them directly. Most people with gardens are familiar with tomato hornworms, which are a native species that become a nocturnal pollinator, the Carolina sphinx moth (Manduca sexta).

As a child many people learn about metamorphosis, that mind-boggling process by which caterpillars miraculously transform from egg, to larva, to chrysalis, and finally into beautiful butterflies or moths. Alongside the concept of metamorphosis is that of the host plant – this caterpillar only eats this plant – and the first fundamental lesson of ecology: that some species cannot complete their life cycles without another species, and in many cases that role cannot be played by a substitute. If you’re very lucky, you may have even had a teacher who raised caterpillars in your classroom.

In a real sense, a core childhood experience with a caterpillar shaped who I am today. Caterpillars spark that desire to want to know more about, and ultimately care for, the natural world – prompting the curious observer to ask “Why does it do this?” “Why does it only eat this plant?” “What else can I find?” But caterpillars are so much more than that.

Like many folks, I began to take gardening seriously at the beginning of the pandemic. Up to that point my efforts had been confined to growing a couple okra plants and some wildflowers in a bed by my back door. I had already decided to start encroaching on the back lawn the previous fall, but when the pandemic hit I expanded my garden plans even further and continued to make the garden bigger every year – some of it for me, and some for wildlife.

I did not set out intending to raise caterpillars that first summer; they simply appeared, and I became captivated. Raising caterpillars became an extension of my goal to grow food, provide an oasis for pollinators and other wildlife, and just generally try to help. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was about to completely consume my life.

A quick internet search revealed the miniscule creatures that had appeared on my dill were a common species – Eastern Black Swallowtails (EBS), Papilio polyxenes, and their host plants are in the carrot (Apiaceae) family. They will eat carrot greens, Queen Anne’s Lace, dill, parsley, cilantro, fennel, and oddly, Rue (Ruta graveolens), which is in the citrus family; but their native host plants include Alexanders (Zizia sp.), Angelicas (Angelica sp.), and Cow Parsnip (Heracleum maximum).

Aside from looking for them a couple times a day, I left the caterpillars alone; but once they reached a certain size, they started disappearing. Caterpillars do not last long in the wild; it turns out they are like hot dogs for birds. They are also targets for parasitoid wasps, praying mantids, and other insect predators. Out of 100 eggs laid, only one may make it to adulthood.

Those are abysmal odds. But if more caterpillars survive to adulthood, that means more butterflies, and ultimately more pollinators for my garden, right?

So I carefully clipped the dill stalks with remaining caterpillars and put them in jars of water, placed a fine-meshed collapsible laundry hamper in my flowerbed, and put the dill bouquets inside. I briefly considered raising the caterpillars indoors, but I didn’t have a good spot for them. This ended up being the right choice, as they can be a little messy, and the caterpillars develop more quickly in warmer temperatures.

The 5 EBS instar stages showing how their colors and sizes change at each stage. Photo credit: Suzanne Tilton

Caterpillars can be raised a number of ways; there is no “right” way. As long as they are protected from predators, provided the correct fresh food plants, and have access to a safe place to make their chrysalis, many methods can be successful. Some people raise them individually in takeout containers; some enclose entire plants or tree branches in protective shrouds or butterfly tents, some use their screened porches. I learned a lot by trial and error, but I ended up sticking with the bouquet-in-a-hamper method. Empty peanut butter jars worked well as vases, until a particularly hard rain resulted in one caterpillar nearly drowning at the bottom of one; so I bought a few narrow mouthed bud vases for my bouquets.

Caterpillars go through 5 instars, or phases. 1st and 2nd instar EBS caterpillars develop very slowly, hardly move, and eat very little. Changing the water in their vases and cleaning out their frass (droppings) every couple of days is sufficient, more often if it’s hot – water in small vases evaporates quickly. As they grow, they need once-daily tending, but by the time they reach their 5th instar they are eating machines! Especially with multiples, I had to clean out the tent and give them a fresh bouquet of greens at least twice and sometimes three times a day. Raising these guys requires growing plenty of herbs for them, but that first year I wasn’t planning to raise caterpillars and was caught short. I had to buy dill at the store to keep them fed (organically grown only – pesticide residue on conventionally grown herbs can kill them!).

A white collapsible laundry hamper being used as a butterfly tent with 11 Black Swallowtail chrysalises hanging inside.

I was surprised by how sedentary they were. They had no inclination whatsoever to explore the tent or leave their bouquets at all, and they tend to stop eating and freeze when they sense movement nearby.

Perhaps most entertaining was their propensity to evert their osmeterium when disturbed. This is a bright orange forked structure vaguely resembling the tip of a snake’s tongue that emerges from their “forehead”. It emits a chemical with a pungent odor something like old cheese or smelly dishrags. They may also headbutt you with their osmeterium to drive the point home, as harmless as it is ridiculous to watch. I’m guessing it also tastes bad. The osmeterium is a characteristic shared by all swallowtail caterpillars, although its color, shape and presumably odor depends on the species. (I call them the Stinky Horns™).

When it’s time for a 5th instar caterpillar to make its chrysalis, the first sign is often a glob of green goo on the floor of the hamper, tent, or container. This is the purging of its digestive tract. The caterpillar will assume a position of repose for a time, then become extremely active, exploring every corner of its container in a single-minded and determined way as it seeks a safe place to hang its chrysalis.

After about a day of exploration, they will settle onto a spot and start spinning a mat of silk on their perch as well as a “belt” around themselves. Once completed, they eventually assume an upside down “J” shape, leaning into their webbing belt, but it takes a few days for them to molt their striped caterpillar skins. Their chrysalises can be brown or green, depending on the color of the surface they chose.

By mid summer I had 6 chrysalises and another dozen caterpillars at all stages of development. Changing the vase water, replenishing the greens, and emptying out the frass was becoming a cumbersome process since I didn’t want to disturb the chrysalises, so I acquired an actual butterfly tent. Now I had one for the caterpillar bouquets, and another to act as the “Pupation Station”. Once the 5th instars purged and became active, I moved them into the round hamper to complete their final stage of development. They are quite easy to handle at this stage and will readily crawl onto a hand or finger, and don’t evert their osmeteria as much.

It takes about 10-20 days for EBS to emerge from their chrysalis. All told, the time from egg to adult EBS takes about 6-8 weeks, depending on temperature, day length, and how much direct sun they are getting. I keep my tents mostly in the shade to slow down the inevitable UV degradation of the tent fabric, but the caterpillars do quite well in direct sun and also develop more quickly. This is especially important in early fall, as the caterpillars must complete the caterpillar stage before their host plants are killed by frost.

Every species of caterpillar is different. Not only do they have different host plants, but they develop at different rates. Monarchs, for example (Danaus plexippus) can only eat milkweeds (Asclepias sp.) and a few others from the same plant family, and their metamorphosis is fast compared to EBS – 10-18 days as a caterpillar, and 1-2 weeks in the chrysalis! They are migratory, and it takes 3 generations to make the journey from their wintering grounds in Mexico and back, so accelerated development is an advantage. Despite their reputation for tasting bad due to their diet on toxic milkweeds, monarch caterpillars are just as susceptible to predation and parasitism as the nontoxic EBS.

One summer I found an Eastern Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes) caterpillar on one of my rue plants, so I raised it in is own vase alongside its EBS cousins. It took quite a lot longer, but it eclosed (emerged) successfully!

Around the end of September, I noticed some of my older caterpillars were almost completely black. I wondered if I had unknowingly raised a different species of swallowtail. (Usually, when EBS molt into their 4th instar, their background color goes from black to green.) Yet another trip to the internet revealed that some EBS stay black in response to the shorter days and decreasing temperatures. Experiments show the trait is heritable, and that darker EBS caterpillars absorb more solar radiation, develop slightly faster, and enter the chrysalis stage up to a few days sooner than their lighter colored counterparts. A few days can make all the difference when the first fall frost is looming! (A link to that study is here.)

I had been releasing butterflies all summer, but by the fall equinox it was clear that no more would be emerging, and the chrysalises in the Pupation Station would be overwintering. I’m often asked if I bring them inside over the winter. No – it is best for them to experience the changing temperatures, seasons, and day length so they receive the cues they need to emerge at the right time.

So the hamper stayed in its spot in the flowerbed next to my back door throughout that unusually snowy winter, getting rained on, snowed on, sleeted on, frozen, thawed, and frozen and snowed on again.

Winter passed, and plants started coming to life again. When would the swallowtails emerge? How would they know it was safe to eclose? It turns out it’s both day length and temperature dependent. In central Ohio, they usually start emerging around Mother’s day and continue through early June. Usually I find my first batch of caterpillars shortly thereafter. And the cycle begins again! I have raised caterpillars on my back stoop every summer since.

So, what’s the point of this? Why should we care about caterpillars?

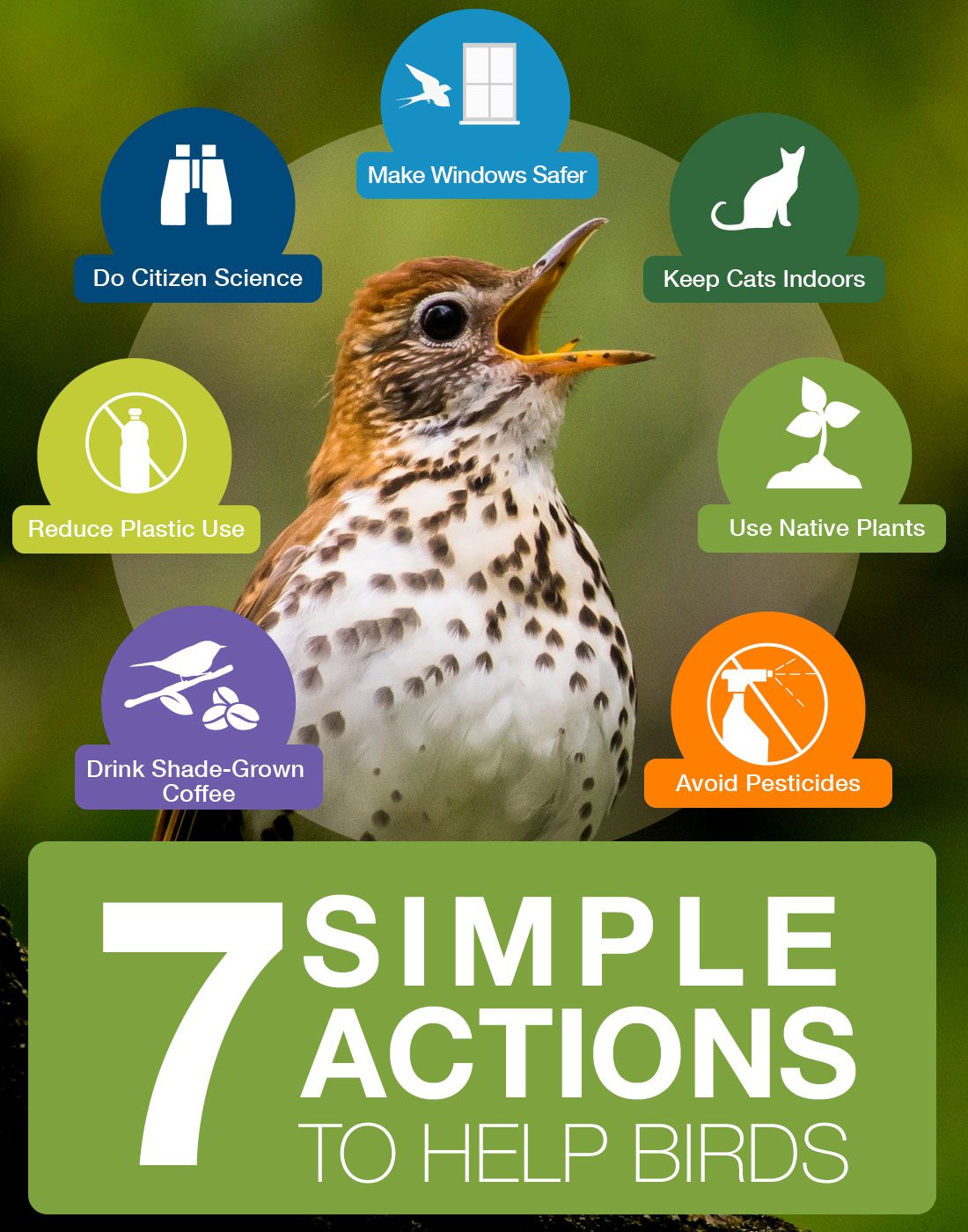

7 simple things to help birds, graphic by Sarah Serrousi. Wood Thrush by John Petruzzi/Macaulay Library.

More information on the Seven Simple Actions to help birds is here. (One of the most effective things you can do to protect birds and other wildlife is to keep your cats indoors. To learn more about why, read my blog here!)

I’ve already mentioned that caterpillars are like hot dogs for birds. Even the seed-eating birds that come to bird feeders need high protein, high fat caterpillars to feed their fast-growing young. No caterpillars, no birds. Songbirds in particular have suffered a 66% decline since the 1960s, and they need all the help they can get! So, saving birds means saving caterpillars, too – even those aggravating tomato hornworms and cabbage worms are important food for birds! But you don’t have to raise caterpillars in tents like I did to make a difference. You may already have a bird feeder or a bird bath in your yard; you can help bring even more birds to your yard by providing habitat for the little “hot dogs”, too.

How can you make habitat for caterpillars? The biggest help is not always easy, but it is simple:

remove invasive plants and replace them with native plants.

A recent meta-analysis found that removing invasive plants and habitat restoration had a six times greater positive impact on conservation than setting aside protected areas. That’s incredible! The greater the variety of native plants, the more attractive it will be to butterflies and moths, especially if you plant sources of nectar as well as their host plants, and the more caterpillars you will have.

Start your own Homegrown National Park! If you own land, start planning for fall planting now. Start small – just chose one area of your yard, assess how much light and moisture it gets, and pick one native tree or shrub and a few perennials suited for those conditions. There are a lot of great resources for native plants (like what to plant and where to get them) at www.OhioNativePlantMonth.org. OSU also has some great resources for creating living landscapes, but if you want to cut straight to the chase, check out this excellent Living Landscape quick guide! If you don’t own land but have a balcony or stoop, choose a few native species you can keep in pots.

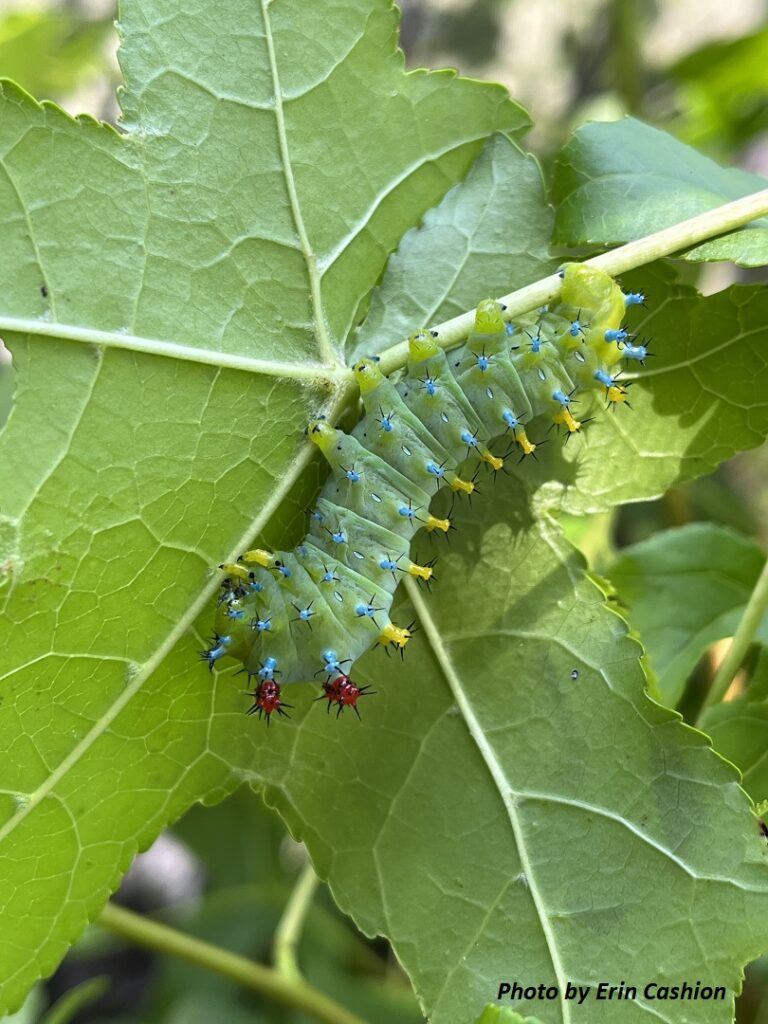

Cecropia moth caterpillar (Hyalophora cecropia) on Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) at a native plant nursery I visited.

Look for invasive plants in your yard and start with the easiest to remove. A few of the most common invasive woody plants used as ornamentals include:

The Ohio Invasive Plants Council maintains an excellent list of great native alternatives to these and other common invasive plants.

Manual removal (pulling) works well for invasives, but if you choose to use herbicides or pesticides in your yard or garden, use them judiciously and always according to label directions. Consider nontoxic alternatives, or eschew them altogether.

Speaking of pesticides, if you’re (rightfully!) worried about mosquitos and the diseases they transmit, make sure you don’t have standing water (even tiny amounts!) around your property. If you have bird or bee baths, clean and refill them at least once a week. If you have rain barrels, you can pop a mosquito dunk in them once a month, which contain a soil bacterium called Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis, or Bti. Bti spores produce toxins that only affect the larvae of the mosquito, blackfly and fungus gnat, and they are safe for humans and other wildlife. You can even make a mosquito trap! These steps are much more effective for mosquito control, and much safer than spraying.

If your municipality sprays for mosquitos, you may be able to request to have your yard excluded from the application. In Columbus, you can call the hotline or make a request through the web or the 311 app. Spraying may be done at night to reduce the impact on day-active pollinators, but most pesticides will be lethal to mosquitos as well as the beneficial insects that we want to keep around, such as lacewings, fireflies, ladybugs, mantids, and of course caterpillars.

Finally, use the Seek or iNaturalist apps to identify and record the plants and animals you find, learn more about the natural world around you, and contribute to community science! Another great app for plant ID is Picture This.

A caterpillar-like Honeysuckle Sawfly larva (Abia lonicerae) on native coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)

Raising caterpillars has reforged a connection to nature that I had been missing and neglecting – not by choice, but simply life happening. Caring for and caring about these little beings is rewarding in a way that is hard to describe. They have rekindled a sense of wonder, appreciation, and discovery. I am paying more attention to plants and the ecosystems they create, and finding cool stuff I could have overlooked before – like firefly and sawfly larvae! The caterpillars themselves are a delight, from their interesting behaviors to the tickle of their little pseudopodia on my fingers. They are such cute little guys. How could I not love them?

Since that first summer of the pandemic, a few things have changed. Last summer our landlord asked us to remove our garden, and the property manager mistook the dill patch for weeds and mowed them down, so I did not raise caterpillars last summer. However, my neighbor grew some dill in pots, so I still ended up overwintering two late-season chrysalises!

I have resorted to keeping native plants in pots, awaiting the time that I can get them into the ground at a place that I own. I am not seeing nearly as many pollinators, birds, or insects around as I did when I had a big garden full of pretty flowers and tasty crops. But I have a potted Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata), which is one of the main host plants for Giant Swallowtails! Maybe I will see some this summer.

I also don’t have as much spare time as I did when I started, so I didn’t plant any dill or parsley in my containers this year. I did not want to attract any EBS since I wasn’t sure if I would have the attention to spare to care for them. But both of the chrysalises I overwintered eclosed successfully, with the earliest ever emergence on April 28 – a full two weeks earlier than usual due to the record-breaking warm spring.

And then, a few weeks later, I got another surprise. Just like that first year, I wasn’t looking for them or trying to attract them, but they appeared anyway.

Here we go again!