A group of researchers from Applied Archaeology Laboratories, Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana has proposed to do a remote sensing survey of the site of St Clair’s Battle on the Wabash River, now mostly within the confines of the modern day town of Fort Recovery, Ohio. Their data recovery plan will use the latest versions of remote sensing instruments including fluxgate gradiometers (a type of a magnetomer), electrical resistance meters, metal detecting and possibly ground penetrating radar. They hope to find areas where specific parts of the battle took place in November of 1791 and to possibly draw conclusions about the movements of both the Indian and the opposing American forces. They also hope to recover locational data about Fort Recovery, the name sake of the town built on the site of St. Clair’s battle by General Mad Anthony Wayne in 1793.The battlefield/fort area, just west of downtown Ft. Recovery, is presently a combination of city owned park lands and private property. However, the topography in the immediate area has been modified to a greater extent over the past century or so adding a certain degree of difficulty to the project. The Wabash River has been re-channeled and earth moved around on the flood plain to forestall river flooding and large portions of both the battle field and the site of Waynes 1793 fort are presently under the town of Fort Recovery itself. Fort Recovery is a typical of numerous small towns built over the last century and a half on the till plains of western Ohio and eastern Indiana and its general placement on the landscape isn’t particularly intrusive but it must be wondered sometimes how well those who were there in the 1790’s would recognize the present lay of the land. Remote sensing surveys like those mentioned above are very effective and have been used successfully at Pickawillany in locating sub-surface features and on pre-historic Hopewell earthwork sites to define ancient construction limits. The task before the Ball State University researchers is daunting and much success is wished their way. However as nothing happens in a vacuum, its necessary to place the Ball State groups proposed efforts within the proper historical context in order to better understand the events that occurred there.

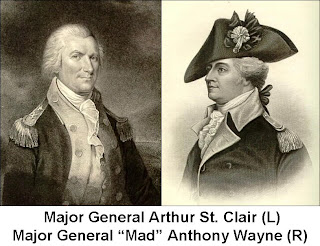

Nearly 220 years ago in the wilderness of what is now western Ohio, the Armed Forces of the United States suffered its worst one day defeat ever. On November 4, 1791, a unified force of Native Americans most likely led by the Miami Chief Little Turtle surprised and annihilated a force of army regulars, levies and Kentucky militia under the command of Major General Arthur St. Clair who later personally described the debacle as unfortunate an action as almost any that has ever been fought. In a three hour period St. Clair’s forces managed to sustain more casualties than did the Americans at both Long Island and Camden, two of the bloodiest encounters of the Revolutionary War and three times the number of killed suffered by George Armstrong Custer in1876 at the Little Bighorn.

In part as a response to Rufus Putnam’s request to provide better protection along the frontier against continued Indian raids and in part to avenge Josiah Harmars rout at the hands of Little Turtle a year earlier at Kekionga (Ft Wayne Indiana) President George Washington charged St. Clair to carry the war into the uncharted Northwest Territory and settle the Indian problem there once and for all. Along with the typical orders that went with organizing such an expedition Washington personally counseled St. Clair not to let his guard down, to keep fortified camps at night and above all else to beware of surprise! On September 17, 1791, St. Clair and his undermanned and less than totally organized army left Fort Washington near Cincinnati to move north into Indian country. Until the later part of October the weather had been seasonably mild if not balmy. On the night of October 31st a tremendous storm passed through the back country, knocking down trees, littering the ground broken limbs and dropping the temperature by several tens of degrees. On the evening of November 3, 1791 and 100 miles into an increasingly arduous march north St Clair’s army found itself encamped on lightly snow covered grounds along the headwaters of the Wabash River near the site of present day Fort Recovery, Ohio. It was nearly dark when St. Clair’s exhausted army reached the Wabash, a location thought by St. Clair to actually be the St. Mary’s River, a tributary of the Maumee that would provide the army a direct route to the heart of the Indian country. Their fatigue aside, the army managed to form into a camp several hundred yards across on a six or seven acre rise of land surrounded by low, wet ground. The army camp consisted of two parallel lines about 70 yards apart with artillery units positioned near the center. Around the nearly one mile perimeter were at least six sentry outposts. With scarcely enough room there for the regular army, the typically unruly militia chose to camp on a slight prominence about 350 yards to the north on the opposite side of the Wabash. Although there was ample evidence of increased Indian activity in the immediate locale St. Clair and his subordinates, it seems, largely chose to ignore it. St Clair was in ill health and all but bed-ridden, suffering from gout and other maladies and his general staff was as enervated as the rest of the army from the ordeals of the long march through the wilderness. Coupled with this were hints of intrigue within the general staff itself toward the commander. Whatever their reasoning the army seemed too tired to feel anything other than secure in their encampment with the Commander-In-Chiefs admonition to beware of surprise! little more than an afterthought.

Little did anyone realize that the surrounding forest concealed the combined force of over a thousand Indian warriors captained not only by Little Turtle but by confederacy of Indian leaders as diverse as the Shawnee Blue Jacket, Chief Tarhe or The Crain of the Wyandots, Delaware Chief Buckongehelas and the Mohawk Joseph Brant. By no means was this tenuous alliance assembled just to harass and make mischief against St. Clair’s army but rather there deeply engaged in an almost desperate defense of their country and of their very existence. They had drawn a line in the sand so to speak and they were going to stand resolutely to it. The attack was well planned and the site well chosen. They knew where the army was, its strengths, its weaknesses and the direction it was headed and they intended to destroy it to the last man.

.

That a large Indian force had amassed in the immediate neighborhood should have been no surprise to St Clair’s army. For some time before dawn on the 4th the Indians in the surrounding forest had filled the air with full throated war whoops obviously meant to intimidate and terrorize the army, especially those in the forward militia camp. As the din continued toward sunrise, one of the militia sentries caught a brief glimpse of a small band of Indians moving quickly through the underbrush ahead of their camp. Fearing it to be part of a larger war party he quickly drew down his musket on the fleeting target and fired. Immediately the forest ahead and to both sides of the militia camp erupted in gunfire at a level never before witnessed by even the most hardened frontier fighter. It was said the militia men fell like leaves and their only estimate of the size of the opposing force was by how rapidly the militia ranks were being thinned by the enemy’s relentless fusillade. Immediately following the opening salvo the Indians charged the militia camp to press their advantage. The Indian attack progressed through the militia bivouac toward the main army in a classic crescent shaped or pincer movement that soon had the army all but surrounded although they still managed to attempt a defensive stand by reforming their lines to face and fire toward the outside. The poorly aimed artillery shots from the center proved useless against a now silent, phantom-like enemy who  made repeated forays into the army’s lines to exact their bloody tribute before just as quickly fading back into the smoky darkness. In the midst of all this, Lt Col. Darke and about 350 levies made a bayonet charge from the artillery position toward the river, momentarily pushing back the attackers. As Darke stopped to regroup his forces it quickly became apparent that the Indians had closed in from behind, cutting his troop off from the main army. To regain their former position the detachment was forced to fight its way back to the high ground in heavy hand to hand combat at the cost of a nearly 90% casualty rate. A survivor later likened the macabre sight of the scalped heads of soldiers lying about the battleground to so many steaming pumpkins in a November cornfield.

made repeated forays into the army’s lines to exact their bloody tribute before just as quickly fading back into the smoky darkness. In the midst of all this, Lt Col. Darke and about 350 levies made a bayonet charge from the artillery position toward the river, momentarily pushing back the attackers. As Darke stopped to regroup his forces it quickly became apparent that the Indians had closed in from behind, cutting his troop off from the main army. To regain their former position the detachment was forced to fight its way back to the high ground in heavy hand to hand combat at the cost of a nearly 90% casualty rate. A survivor later likened the macabre sight of the scalped heads of soldiers lying about the battleground to so many steaming pumpkins in a November cornfield.

His illness and gout notwithstanding St. Clair was quick to mount and make his presence known on the battlefield as he moved up and down the lines shouting commands and words of encouragement to those who continued to fight and goading as cowards those whose only concern was seeking cover wherever it could be found. With the situation utterly and completely out of hand, retreat was sounded and lines were formed to move south back along the trail toward Ft. Jefferson near present day Greeneville, the same trail that brought them to the banks of the Wabash just a few hours earlier. In a move of sheer desperation, Lt. Col Darke led a final bayonet charge into the mass of Indians as they closed in on the south. The sudden fury of this all or nothing maneuver completely overwhelmed the Indians in the path of the charge and they were quickly pushed back several hundred feet beyond the Ft Jefferson trail. This breeched the attackers lines long enough to allow those who could make it to escape back toward Ft Jefferson. The breakout soon became a flight of panic as the Indians recovered from their unexpected start and took after the escaping army, many of whom were riding two or three to a horse. The pursued lightened their loads by throwing down anything that might burden them as they ran. Shoes were cast off because they provided no traction in the slick, mudded snow. Muskets were repeatedly smashed against trees to keep them from falling into the hands of the enemy and all sorts of military trappings were cast aside. At the same time there are numerous accounts of complete strangers unselfishly helping each other in their attempt to escape. In addition to the soldiers and militia there were several dozen non-military personnel traveling with the army including wives, children and other assorted camp followers. Their status as non-combatants didn’t seem to matter as many if not most were killed and/or otherwise never seen again.

One notable exception was a tall, statuesque woman with flaming red hair known only as Red Haired Nance. She had become separated from her infant child during the battle although quite likely it was taken and raised by the Indians as it was commonly known to occur. However, not only did Nance manage to keep her exceptional tresses when so many others were losing theirs but eventually settled in Cincinnati and lived there to an old age, often relating to all that would listen her account of that harrowing day.

The Indians continued their pursuit for another few miles but soon returned to the battlefield to see what could be plundered from the literally tons of material abandoned there. St Clair, his clothes pierced by musket balls and a lock of his hair shot away was said to be the last to leave the battlefield. Although his exit astride a broken down pack horse made for a rather inglorious departure it should be noted that during the battle he had at least three mounts shot out from under him. Absent what might be said about his ineptness and being unfit for command, he was certainly no coward. The battle was over in about three hours and the complete and utter destruction of men and materiel created a scene more easily imagined than described. Six hundred and thirty seven of the nearly 1400 present were killed including 69 of the 124 commissioned officers although some accounts estimate American causalities as closer to 900. The Indians fared much better with only 21 killed and 40 wounded.

St Clair was brought up on charges for the debacle at the Wabash but was eventually exonerated for a number of extenuating circumstances. He remained the Governor of the Northwest Territory until 1802 and died virtually destitute in 1810 at the age of 84. Much has been made of exactly why St. Clairs defeat was so dramatically one sided. For decades if not centuries it has been explained that for numerous and varied reasons and excuses St. Clair had lost the battle far more than the Indians could have ever won it; that he certainly must have been absolutely inept to be so soundly whipped by savages. Another school of thought is that St Clair and his army was soundly whipped by a well coordinated force employing superior tactics and led by an acknowledged supreme commander and a hierarchy of able field commanders who were able to set aside cultural norms and practices, albeit temporarily, for the benefit of the whole. Given the circumstances of the battle and the strength and composition of enemy he faced it was almost as if it were pre-ordained that St. Clair would fail. When later charged that his loss was due in great part to the fact that he had detached a large portion of his forces prior to the battle to run down deserters, St. Clair told the Congressional investigators in all candor that the battle would have still ended much the same only with more causalities. To read more on this view see Leroy V. Eid, American Indian Military Leadership: St. Clairs 1791 Defeat in The Journal of Military History, Vol. 57, No. 1 (January 1993).

In late 1793 the site of St. Clairs defeat was recovered by the forces of General Mad Anthony Wayne, known to the Indians as the Chief Who Never Sleeps. In early 1794 a substantial wooden stockade was erected there and aptly named Fort Recovery in honor of its “recovered” location. In the summer of that year Ft. Recovery was attacked by a force of upwards of 2,000 Indians from various Great Lake tribes, the greatest massed force of Indians ever assembled to that point in time to oppose an American army. In a pitched two-day battle the Indians and their British allies were this time turned back with heavy casualties, greatly aided by the fortified position held by the Americans. Wayne pushed on from here to the Maumee where he achieved a final victory over the united tribes in northwest Ohio in a battle known as Fallen Timbers making way for the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795 and the ceding of tremendous areas of Indian lands in Ohio to the American government. It has been proposed that one reason Wayne was so successful in his Maumee Campaign was that the tenuous alliance that worked so well at St. Clair’s Defeat and again in the siege of Fort Recovery was gone. Although the Indians failed to take the fort it was due more to the strength of the Americans fortified position rather from shortcomings in the execution of a concise battle plan. It would appear that the cohesion that held the united tribes together up to Fallen Timbers had completely broken down without any semblance of recovery until the War of 1812.

For further reading see Historical Sketch of Fort Recovery published by the Fort Recovery Historical Society Inc. Also see The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812 by Benson J. Lossing 1869

The Strange Case of Roger Vanderburg

In a copy of Henry Howes Historical Collections of Ohio I purchased some time ago I found an old newspaper clipping about a fellow who managed to escape death at St Clair’s defeat only to meet an even more bizarre fate. Since then I have seen several permutations of the article including the text as copied below but with more or less detail. I should add that the rosters at Valley Forge don’t list a Roger Vandeburg nor is anyone of that name found to be associated with General Washington’s staff or with St. Clair’s army. Nor is there a Vandeburg family living in the Lancaster Pa. vicinity during the Revolutionary War or by the first Federal Census in 1790. It all may be a rendering of an early version of an omnipresent urban myth mixed with a retelling of an older tale. I guess you’ll have to be the judge but all I can say is what a way to have to go.

‘A Curious Discovery’

The hurricane which passed over the Miami Valley on July 4 tore down a number of old trees, and amongst them a large oak. The owner of the property, a Mr. Rogers, on examining the extent of the damage done by the storm, discovered in the hollow of the fallen oak a human skeleton, with some brass buttons and shreds of clothing, and among other things a pocket-book with a number of papers. A communication to the Miami County Democrat,” signed J. F. Clark relates: The man’s name, as gathered from the papers, was Roger Vanderburg, a native of Lancaster Pennsylvania and a captain in the Revolutionary Army. He was an Aid to Washington during the retreat across the Jerseys, and served a time in Arnold’s head-quarters at West Point. In 1791 he marched with St. Clair against the North-western Indians, and in the famous outbreak of that General on the Wabash. November 3 of the year just written, he was wounded and captured. But while being conveyed to the Indian town at Upper Piqua he affected his escape, but found himself hard pressed by his savage foes. He saw the hollow in the oak, and despite the mangled arm, and with the aid of a beech that grew beside the giant then, he gained the haven and dropped therein. Then came a fearful discovery. He had miscalculated the depth of the hollow, and there was no escape. Oh, the story told by the diary of the oak’s despairing prisoner! How, rather than surrender to the torture of the stake, he chose death by starvation; how he wrote his diary in the uncertain light and the snows! Here is one entry in the diary: ‘November 10. Five days without food! When I sleep I dream of luscious fruits and flowing streams. The stars laugh at my misery! It is snowing now. I freeze while I starve. God pity me! ‘. The italicized words were supplied by Mr. Rogers, as the trembling hand oft- times refused to indite plainly. The entries covered a period of eleven days, and in disjointed sentences is told the story of St. Clair’s defeat. Mr. Rogers has written to Lancaster to ascertain if any descendants of the ill- fated captain live; if so, they shall have his bones.

Bill Pickard