Earlier I provided a brief history of how that magnificent earthwork just south of Newark known as the Great Circle managed to survive the onslaught of progress and civilization over the past two centuries first by serving both as a state and county fairgrounds and then as Idlewilde Park, sort of a forerunner of the Cedar Point/Kings Island amusement venues of today. It’s possible that much of its survivability in those days was due in large part to its mystique as the Old Indian Fort as anything else of a more noble nature. A reporter from a Columbus newspaper, writing in 1877, declared that “Licking County can rightfully lay claim to the finest Fair Grounds, all things considered, in the State.” He remarked upon the “splendid shade trees,” the excellent display of stock, and the extravagantly beautiful Floral Hall, but he was especially charmed by the mysterious “circular earthwork overlooking the track and grounds.” But what of the history of the Great Circle history before the Euro-American concept of its history began?

It lay more or less fallow for nearly two millennia before it was discovered by early settlers, but it must have truly been a sight to behold in its original condition. Obviously, for the builders to have invested so much labor, it had to have been a place of notable importance, a sacred place, a festive place where achievement was celebrated, a place of obligation and commemoration and a gathering place for esteemed and prominent leaders. The ceremonies and pageantry that took place there in the distant past can only be imagined. The last fair was held at the Great Circle in September of 1933. That same year Emerson F. Greenman of the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society began restoration of the earthwork in an attempt to return it to at least a semblance of its long past former self. It was the height of the Great Depression and his crew was made up largely of city unemployed paid from the Newark Relief Fund. Well into the 20th century the Great Circle continued to see its share of use and abuse as a county fairgrounds and finally as an amusement park and I have been told that as late as 1932 the race track remained a favored venue for motorcycle racing. It was about time to treat the Great Circle with the respect due such a magnificent example of human endeavor. As could be expected the restoration work at the Great Circle went slowly at first but good things are worth waiting for. However, going back to an earlier time, a time when the public seemed to be proudly content with county fairs and other recreational diversions at the site of the Old Indian Fort and there are two events in particular that bear mention and rise above what might seem to be the sites then typical uses.  In October 1861 Camp John Sherman was established at the Great Circle as a training installation for the 76th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. John Sherman was a noted judge and politician in Ohio at that time and younger brother of General William Tecumseh Sherman. The regiment shipped out in early February 1862 and was involved in heavy action just six days later at Fort Donelson,. The 76th served in exemplary fashion throughout the war having been engaged in 47 battles, while covering more than 9,000 miles of march. The unit was disbanded in July of 1865. On July 22, 1878 the 76th assembled one more time at the Great Circle as hosts of the Grand Reunion of the Veteran Soldiers and Sailors of Ohio. Between 15,000 and 20,000 veterans and friends were in attendance. Among the invited dignitaries that day were President Rutherford B. Hayes, General James A. Garfield, General William T. Sherman and Ohio Governor Richard M. Bishop. A speakers platform was built at the site of the Eagle Mound and as the veterans and others eagerly jammed into the circle to witness the proceedings.

In October 1861 Camp John Sherman was established at the Great Circle as a training installation for the 76th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. John Sherman was a noted judge and politician in Ohio at that time and younger brother of General William Tecumseh Sherman. The regiment shipped out in early February 1862 and was involved in heavy action just six days later at Fort Donelson,. The 76th served in exemplary fashion throughout the war having been engaged in 47 battles, while covering more than 9,000 miles of march. The unit was disbanded in July of 1865. On July 22, 1878 the 76th assembled one more time at the Great Circle as hosts of the Grand Reunion of the Veteran Soldiers and Sailors of Ohio. Between 15,000 and 20,000 veterans and friends were in attendance. Among the invited dignitaries that day were President Rutherford B. Hayes, General James A. Garfield, General William T. Sherman and Ohio Governor Richard M. Bishop. A speakers platform was built at the site of the Eagle Mound and as the veterans and others eagerly jammed into the circle to witness the proceedings.  Part way through the program, the platform began to collapse and President Hayes and General Sherman, according to an account published in the Cincinnati Enquirer, “only saved themselves by springing forward out of their chairs, which tumbled back into the ruins.” Disaster was averted and Newark spared the infamy of being responsible for the deaths of both a US president and a favorite son Civil War hero. It has been alleged that Sherman was later heard to remark something to the effect that in a single afternoon one drunken carpenter nearly accomplished what 400,000 Rebels with loaded muskets failed to do in four years. Such is life.

Part way through the program, the platform began to collapse and President Hayes and General Sherman, according to an account published in the Cincinnati Enquirer, “only saved themselves by springing forward out of their chairs, which tumbled back into the ruins.” Disaster was averted and Newark spared the infamy of being responsible for the deaths of both a US president and a favorite son Civil War hero. It has been alleged that Sherman was later heard to remark something to the effect that in a single afternoon one drunken carpenter nearly accomplished what 400,000 Rebels with loaded muskets failed to do in four years. Such is life.  Just six short years later on October 13, 1889 the Great Circle was the backdrop for William F. Cody and Buffalo Bills Wild West, perhaps the greatest entertainment extravaganza of its day. The Wild West was a grand celebration of horsemanship combined with an array of cowboys, scouts, shootists and

Just six short years later on October 13, 1889 the Great Circle was the backdrop for William F. Cody and Buffalo Bills Wild West, perhaps the greatest entertainment extravaganza of its day. The Wild West was a grand celebration of horsemanship combined with an array of cowboys, scouts, shootists and  Brawny Braves of Bloody Records. A handbill for the show claimed that it had the “largest delegation of wild Indians ever brought east.” The show was replete with re-enactments of cavalry charges, the riding of the Pony Express, wagon train attacks and buffalo hunts. The performance would often end with a rendition of Custers Last Stand with Cody himself in the fatal lead role. In the inset Cody is seen posing with the great Sioux Chief Sitting Bull, who by then had sadly been reduced to a grand character in the Wild West.

Brawny Braves of Bloody Records. A handbill for the show claimed that it had the “largest delegation of wild Indians ever brought east.” The show was replete with re-enactments of cavalry charges, the riding of the Pony Express, wagon train attacks and buffalo hunts. The performance would often end with a rendition of Custers Last Stand with Cody himself in the fatal lead role. In the inset Cody is seen posing with the great Sioux Chief Sitting Bull, who by then had sadly been reduced to a grand character in the Wild West.  In an odd artifact of history, the Wild West happened to be witnessed that day in Newark by none other than a young Warren K. Moorehead. Moorehead would go on in life to be celebrated in his own right as an antiquarian, early student of archaeology, author, academic and defender of Native American rights. Recognizing the buffalo as the lifeblood of the Plains Indians he was shocked and dismayed at the treatment received by the buffalos in what he saw as somewhat of a burlesque-like pageant. In his 1914 book The American Indian in the United States, Period 1850-1914 Moorehead related the following: At Newark, Ohio in the early 80’s when a boy, I attended Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. I shall ever remember my sensations when witnessing the grand buffalo hunt. Three or four poor

In an odd artifact of history, the Wild West happened to be witnessed that day in Newark by none other than a young Warren K. Moorehead. Moorehead would go on in life to be celebrated in his own right as an antiquarian, early student of archaeology, author, academic and defender of Native American rights. Recognizing the buffalo as the lifeblood of the Plains Indians he was shocked and dismayed at the treatment received by the buffalos in what he saw as somewhat of a burlesque-like pageant. In his 1914 book The American Indian in the United States, Period 1850-1914 Moorehead related the following: At Newark, Ohio in the early 80’s when a boy, I attended Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. I shall ever remember my sensations when witnessing the grand buffalo hunt. Three or four poor  old scarred bison were driven into the fair ground enclosure by some whooping cow punchers. Buffalo Bill himself dashed up alongside the lumbering animals and from a Winchester repeater discharged numerous blanks into the already powder burned sides of the helpless creatures. The crowd roared with appreciation as the cow punchers pursued and rounded up the hapless bison. Before the grandstand, Buffalo Bill reined in his steed and spurring the horse so he would prance bowed to the right and to the left. Professor Hornady’s report together with other information indicates that enough buffalo were carted about the East to have formed a very respectable herd had they been permitted to remain in some favored spot in the buffalo country. During a later visit to Newark, Buffalo Bill told a reporter for the Newark Daily Advocate that the Newark Earthworks were the most wonderful mounds in existence. Oddly enough no one apparently thought to record what the western Indians thought about the earthworks built by their ancient brethren. Such is life, part II.

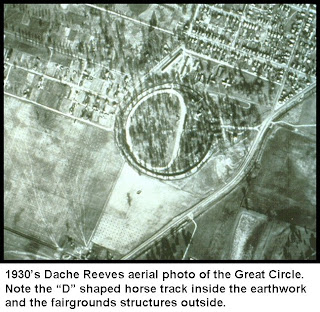

old scarred bison were driven into the fair ground enclosure by some whooping cow punchers. Buffalo Bill himself dashed up alongside the lumbering animals and from a Winchester repeater discharged numerous blanks into the already powder burned sides of the helpless creatures. The crowd roared with appreciation as the cow punchers pursued and rounded up the hapless bison. Before the grandstand, Buffalo Bill reined in his steed and spurring the horse so he would prance bowed to the right and to the left. Professor Hornady’s report together with other information indicates that enough buffalo were carted about the East to have formed a very respectable herd had they been permitted to remain in some favored spot in the buffalo country. During a later visit to Newark, Buffalo Bill told a reporter for the Newark Daily Advocate that the Newark Earthworks were the most wonderful mounds in existence. Oddly enough no one apparently thought to record what the western Indians thought about the earthworks built by their ancient brethren. Such is life, part II.  Restoration work at the Great Circle began in earnest in 1934 with the arrival of Civilian Conservation Corps( CCC) Company #1544 at Camp Licking-Moundbuilders. Company #1544 numbered 220 veteran enrollees and was soon busy removing fairgrounds buildings and other remnant structures as well as restoring the earthwork walls and grounds in general. About that time Dache Reeves of the US Army Air Corps captured the accompanying aerial image of the Great Circle with the fairgrounds buildings and the remnants of the pony track still visible. The CCC restoration

Restoration work at the Great Circle began in earnest in 1934 with the arrival of Civilian Conservation Corps( CCC) Company #1544 at Camp Licking-Moundbuilders. Company #1544 numbered 220 veteran enrollees and was soon busy removing fairgrounds buildings and other remnant structures as well as restoring the earthwork walls and grounds in general. About that time Dache Reeves of the US Army Air Corps captured the accompanying aerial image of the Great Circle with the fairgrounds buildings and the remnants of the pony track still visible. The CCC restoration  work continued into 1936. In 1937 approximately 6.1 acres at the Great Circle Earthworks was deeded to the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society by William and Laura Wehrle and Augustine Wehrle and thus was created the parklike reservation we see today. The first scientific exploration of the Great Circle wall took place in the summer of 1992. A relatively narrow trench was excavated on the north side of the earthwork, that side of the Circle closest to the fairgrounds out buildings and that part of the Circle that had been subject to the most abuse and degradation during that time. In the accompanying inset the results are seen as distinct layers. No artifacts or burials were encountered during the project which, it should be stated, wasn’t the point of the excavations in the first place. The excavators were much more interested in how and when the earthwork was constructed. What was gleaned from the excavations was that original construction took place somewhere about 160 BC over a truncated prairie soil that had been cleared of the uppermost layers of grass and soils. These strata contained the contaminants such as bugs, worms and

work continued into 1936. In 1937 approximately 6.1 acres at the Great Circle Earthworks was deeded to the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society by William and Laura Wehrle and Augustine Wehrle and thus was created the parklike reservation we see today. The first scientific exploration of the Great Circle wall took place in the summer of 1992. A relatively narrow trench was excavated on the north side of the earthwork, that side of the Circle closest to the fairgrounds out buildings and that part of the Circle that had been subject to the most abuse and degradation during that time. In the accompanying inset the results are seen as distinct layers. No artifacts or burials were encountered during the project which, it should be stated, wasn’t the point of the excavations in the first place. The excavators were much more interested in how and when the earthwork was constructed. What was gleaned from the excavations was that original construction took place somewhere about 160 BC over a truncated prairie soil that had been cleared of the uppermost layers of grass and soils. These strata contained the contaminants such as bugs, worms and  toads the stuff of the ordinary, profane world that certainly didn’t belong in the harmony or order they were trying to achieve. And it should be remembered that earthworks are in fact constructed, that is with a definite theme and purpose in mind according to a preferred set of guiding principles. By no means are they just haphazard piles of soil or simply elongated berms used to define a social space. It has also often been wondered by those who think of such things just how the original builders were able to clear the ancient forests that likely covered earthwork sites in order to construct their spectacular monuments. In the case of the Great Circle at least it would appear that needn’t have happened. Pollen analysis and the presence of a truncated prairie soil at the base of the structure amply demonstrates that at the time of construction the land form was an open, savannah-like pocket prairie likely interspersed with small clusters of oak trees. There was no forest to get in the way. The project also confirmed that the so-called Salisbury Wall actually existed, at least where it was tested for. The Salisbury Wall was a low earthen embankment that circumscribed the Great Circle noted only on an early map authored in the mid 1800’s by brothers James and Charles Salisbury. However, it should be noted all weren’t totally thrilled with the overall project, neither in concept nor in practice. Part way through the excavation a group of Native Americans made their feelings known and staged a protest stating their displeasure. After a certain amount of negotiating, the protesting group was invited to conduct a prayer ceremony at the site to assuage the spirit of the ancient builders and the project was allowed to proceed to conclusion.

toads the stuff of the ordinary, profane world that certainly didn’t belong in the harmony or order they were trying to achieve. And it should be remembered that earthworks are in fact constructed, that is with a definite theme and purpose in mind according to a preferred set of guiding principles. By no means are they just haphazard piles of soil or simply elongated berms used to define a social space. It has also often been wondered by those who think of such things just how the original builders were able to clear the ancient forests that likely covered earthwork sites in order to construct their spectacular monuments. In the case of the Great Circle at least it would appear that needn’t have happened. Pollen analysis and the presence of a truncated prairie soil at the base of the structure amply demonstrates that at the time of construction the land form was an open, savannah-like pocket prairie likely interspersed with small clusters of oak trees. There was no forest to get in the way. The project also confirmed that the so-called Salisbury Wall actually existed, at least where it was tested for. The Salisbury Wall was a low earthen embankment that circumscribed the Great Circle noted only on an early map authored in the mid 1800’s by brothers James and Charles Salisbury. However, it should be noted all weren’t totally thrilled with the overall project, neither in concept nor in practice. Part way through the excavation a group of Native Americans made their feelings known and staged a protest stating their displeasure. After a certain amount of negotiating, the protesting group was invited to conduct a prayer ceremony at the site to assuage the spirit of the ancient builders and the project was allowed to proceed to conclusion.  In the past 200 or so years events at the Great Circle have included the gathering of folks to celebrate their achievements as well as the gathering of folks for camaraderie and relaxation. There have also been grand expositions of spectacular prowess and the telling of tall tales about life elsewhere. Some have found cause to marshal their forces there to go out in defense of their society, as it was their duty, to hopefully return and feted as heroes and celebrated by important dignitaries. There has also been a certain amount of rancor and discontent in the goings on. Aside from the extraordinary there has also been the ordinary. There have been picnics and weddings and family reunions at the Great Circle. High school and college graduations have been celebrated there as individuals move through another of life’s stages toward becoming productive members of society; those who have already lived full and productive lives and have passed on have been eulogized there. All in all there has likely been a celebration on the grounds of the Great Circle for any life occasion that can be imagined. We have no way of knowing what types of ceremonies took place at the Great Circle in ancient times but I cant help but wonder at times if there isn’t a large degree of commonality in all this past and present, a thread that ties together the long history of events at the Great Circle, the then and the now; perhaps not by type but by theme and/or circumstance. Just food for thought.

In the past 200 or so years events at the Great Circle have included the gathering of folks to celebrate their achievements as well as the gathering of folks for camaraderie and relaxation. There have also been grand expositions of spectacular prowess and the telling of tall tales about life elsewhere. Some have found cause to marshal their forces there to go out in defense of their society, as it was their duty, to hopefully return and feted as heroes and celebrated by important dignitaries. There has also been a certain amount of rancor and discontent in the goings on. Aside from the extraordinary there has also been the ordinary. There have been picnics and weddings and family reunions at the Great Circle. High school and college graduations have been celebrated there as individuals move through another of life’s stages toward becoming productive members of society; those who have already lived full and productive lives and have passed on have been eulogized there. All in all there has likely been a celebration on the grounds of the Great Circle for any life occasion that can be imagined. We have no way of knowing what types of ceremonies took place at the Great Circle in ancient times but I cant help but wonder at times if there isn’t a large degree of commonality in all this past and present, a thread that ties together the long history of events at the Great Circle, the then and the now; perhaps not by type but by theme and/or circumstance. Just food for thought.

Bill Pickard