New Collection Spotlight: Justice; Clothing Just for Girls

The Ohio History Connection is thrilled to have recently obtained a collection of over 60 items of Justice and Brothers clothing ranging from 2008 to 2017.

It is indeed about time. It’s about the Ice Age, which was from 2.6 million to about 11,700 years ago. This seems like a long time ago but in geologic terms, in the over 4.5 billion history of the earth, it’s the blink of an eye. It’s also about time – time that someone finally found the newest Ice Age carnivore in Ohio! Those of us interested in the fauna of the Ice Age (or Pleistocene epoch) are always on the lookout for the Big Two; the two large carnivores that we think lived in what is now Ohio but whose remains have not yet been found here. Can you guess what these species are? Many people can name one of them, the legendary saber-toothed cat. But the other species is less well known, at least until Game of Thrones thrust it into popularity: the dire wolf!

Gray wolves tangle with dire wolves over a bison carcass. Illustration by Mauricio Anton.

Before you get too excited and plan your family’s next vacation around going to see this newest Ice Age carnivore find, it’s not an entire skeleton on display in a museum. It’s not even a whole skull. It’s just one tooth, and not even an impressive canine tooth, just a smaller front tooth, an incisor. Well, it’s not even a whole tooth, just the root of the incisor. But it still got me more excited than a whole season of Game of Thrones! It was found during excavations of the Sheriden Cave Site, part of the Indian Trail Caverns in northwestern Ohio, near Carey in Wyandot County. First excavated in 1990 by Dr. Greg McDonald, then of the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History, Sheriden Cave is one of the richest Pleistocene sites in Ohio. The site has produced over 75 species of Pleistocene animals, and also includes evidence of Paleo-Indian occupation of the cave from 11,000 – 12,000 years ago.

So why has it taken so long to find the dire wolf in Ohio!? Dire wolves were one of the most common and most widespread carnivores in North America during the Pleistocene, ranging from coast to coast, from Florida and Mexico to southern Canada. Many of Ohio’s other large Ice Age mammals were uncovered years ago in the state. Species like mastodons, mammoths, giant beavers and ground sloths have been known to science for a long time. But notice that these species are all herbivores, and they are much more common than the carnivores that prey on them. It takes a lot of individuals of a prey species to support each carnivore. I think another reason that dire wolf or saber-tooth remains haven’t been found here yet is because of size. We often think of the Ice Age mammals as being large. But the dire wolf was only a little larger than the modern gray wolf. Most Pleistocene mammal remains are initially found not by careful excavation but more by accident, such as when someone is digging for a farm pond or finds a bone or tooth eroding out of a stream bank. Unless the specimen is particularly large it can easily go unnoticed. Also most carnivore remains that have been discovered in Ohio were found in caves or sinkholes, rather than from digging into the Pleistocene deposits. Maybe someone has come across a dire wolf or saber-tooth cat skeleton and, not finding the skull, thought it was just a dog or a deer.

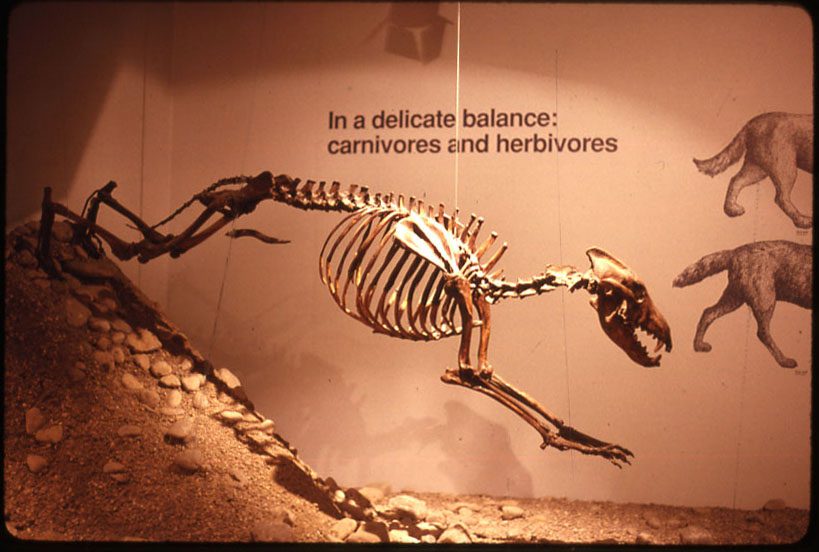

Skeleton of a dire wolf in a jumping pose. D. Dyer photo.

When I first heard that a single incisor of the dire wolf was found at the Sheriden site, I wondered how did they know it was a dire wolf and not a gray wolf? While living in Montana I worked on trying to distinguish wolf remains from large modern dogs. Often they were difficult to tell apart, and I surely wouldn’t try to conclusively identify a large canid from half an incisor! It turned out that the researchers extracted DNA from the tooth root and were able to positively identify that it was from a dire wolf.

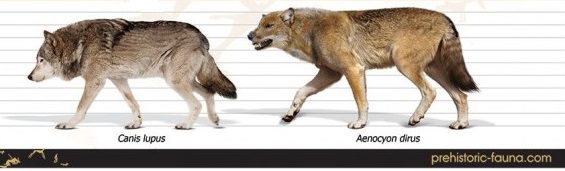

The dire wolf (right) compared to a gray wolf. Illustration by Roman Uchytel.

So what’s the difference between our modern gray wolf and the dire wolf? As I mentioned, dire wolves weren’t much larger. They were about the same size as today’s largest wolves which are found in Alaska and northwest Canada. Dire wolves averaged between 130 – 150 pounds while the average weight for modern wolves is about 100 pounds for females and 120 pounds for males, but the largest males can range up to 175 pounds. There were actually two subspecies of dire wolves in North America. The western subspecies was smaller while the eastern subspecies, which would have lived in Ohio, was larger. The dire wolf, though only a little larger than the wolf, was more robust. It had stronger limbs and a more massive head, and most significantly had larger carnassials – which are large, paired upper and lower teeth found in many carnivores. Often called the carnassial pair, they consist of the 4th upper premolar and lower 1st molar and are adapted to shear flesh and crush bone. These carnassials were more massive in the dire wolf. Scientists have determined that the dire wolf had the greatest bite force at the canine teeth of any closely related dog species. Traits such as large carnassials and a strong bite force reflect the diet of the dire wolf. They were social, group hunters like the gray wolf and preyed on large species that would be difficult to take down such as horses, camels, bison, and giant ground sloths. For big prey you need big teeth!

Gray wolf mandible (front) compared to the more robust dire wolf mandible. OHC photo.

Close-up showing the larger lower 1st molar (carnassial) of the dire wolf. OHC photo.

Dire wolves have always been called “wolves” since their appearance and habits closely resemble the gray wolf. However, a major study of dire wolves appeared this year in the journal Nature. This new study not only documented the first specimen from Ohio, it also determined that dire wolves are not wolves after all. The scientists did a detailed analysis of the genetics of the dog family and concluded that dire “wolves” were actually quite different than gray wolves. The dire wolf ancestral line diverged from that of wolves and coyotes some 5.7 million years ago. The study also showed that dire wolves originated in the Americas, while the ancestors of wolves and coyotes evolved in Eurasia and colonized North America only about 20,000 years ago. Though they overlapped in time, the genetics proved that no hybridization took place between dire wolves and American gray wolves or coyotes. There is a great deal of interbreeding between other members of the genus Canis. The lack of genes of other canids in the dire wolf lineage is more evidence to indicate their significant genetic difference.

This study further recommends that the long-held scientific name of the dire wolf, Canis dirus, should now be changed to reflect that it is not closely related to the other members of the genus Canis. Now it’s placed in a new genus and the correct name is Aenocyon dirus. Though it went extinct near the end of the Ice Age, it still lives up to its new name Aenocyon, which in Ancient Greek means “terrible wolf”. But no animal is actually “terrible” (except maybe ticks!). All have their place in the larger ecosystem in which they live, fine-tuned by millions of years of evolution.