Mary Stuart Andrews stepped out of the house in a white lace blouse with coordinating white lace jacket and a sash pinned across her body. Perhaps she met up with friends, also dressed in white, drawing the attention of every passer-by. What did they talk about as they headed to their first parade in support of women’s suffrage? Did Andrews stand tall as she passed neighbors on the street? Did she have any reservations about what she was about to do?

Andrews, a 39-year-old single woman, was a native of Warren, Ohio, where she worked as Secretary of the Ohio Woman Suffrage Association under the formidable Harriet Taylor Upton. She and thousands of women in Ohio literally took to the streets starting in 1912 to publicly demand the right to vote. They donned white to garner press coverage of their parades and their demands; the white clothing would look appealing when printed in black and white, which organizers hoped would make newspaper editors more likely to include them—and coverage of their protests—in their publications.

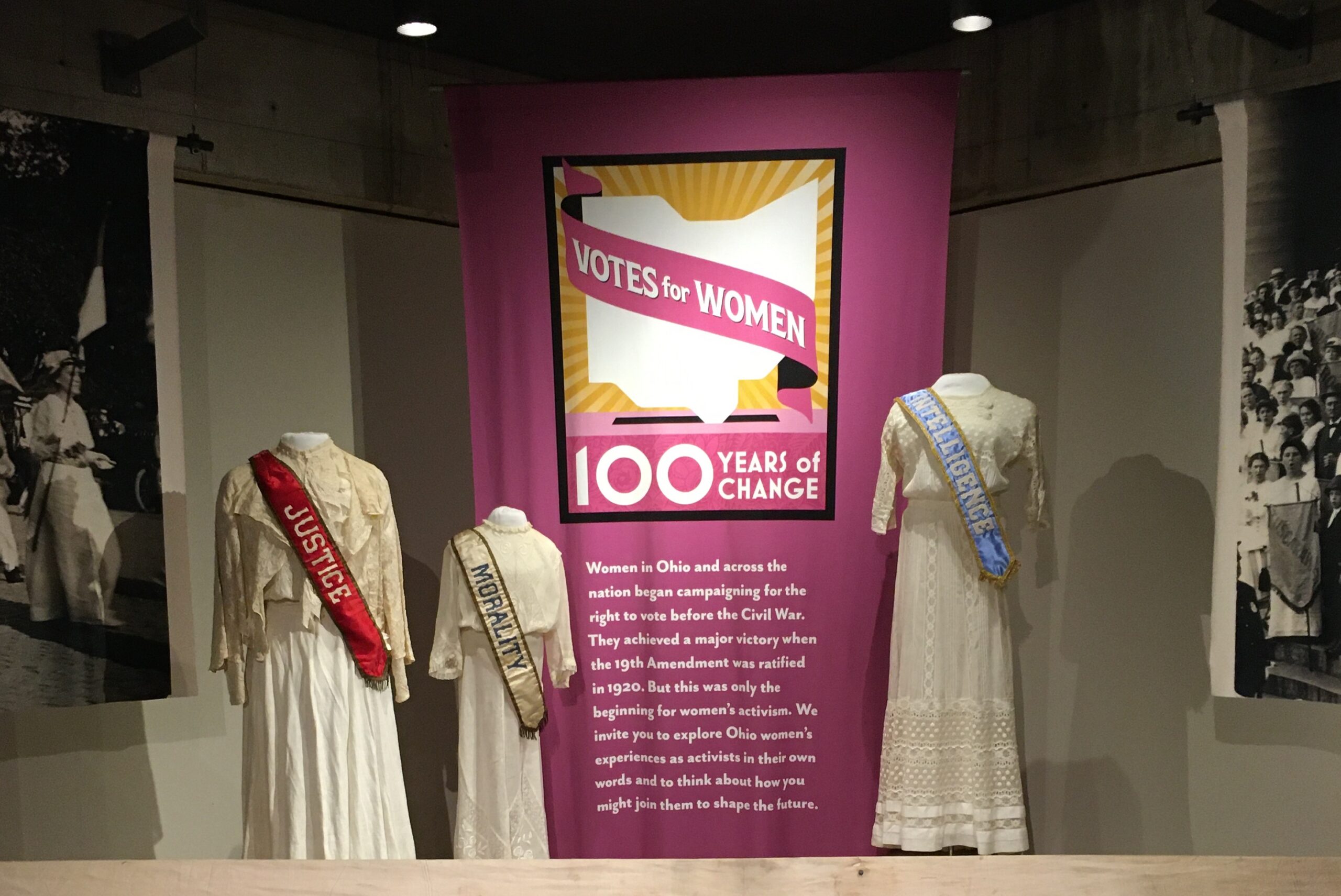

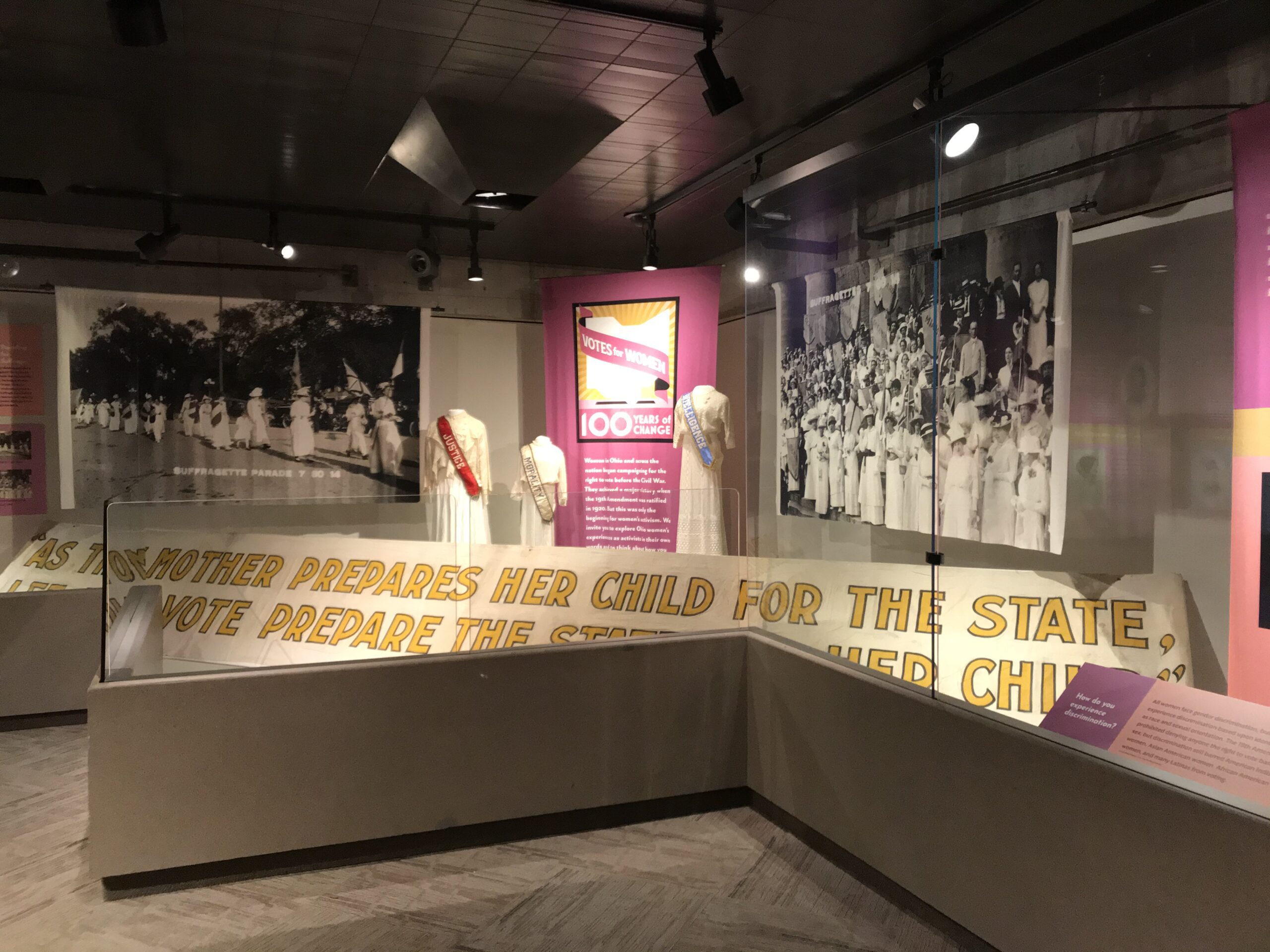

Mary Andrews’s original parade blouse and jacket and “Justice” and “Morality” sashes are included in the exhibit at the Ohio History Center.

Andrews would have marched in tandem with two other women, each wearing a sash bearing the word “intelligence,” “justice,” and “morality.” The three words were a tribute and a nod to pioneer women’s rights and suffrage activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who stated, “If intelligence, justice, and morality are to have precedence in the Government, let the question of the woman be brought up first….” The sentiment was a popular one among suffragists who purported that women’s role as mothers responsible for raising their children into good, moral adults would make valuable contributions to the political realm along those same lines. How could mothers raise children in a society whose policies they could not shape?

The exhibit includes a suffrage banner made by the Columbus Sign Company of Columbus, Ohio. It reads, “As the mother prepares her child for the state, let the vote prepare the state for her child.” The banner was made in 1910 and used at Memorial Hall, also in Columbus.

But these sentiments gloss over the divisive campaign for women’s suffrage. Stanton’s quote is often repeated in the format above, with the last six words excluded: “…and that of the Negro last.” Some women, including Stanton, worked against securing suffrage for Black men under the 14th (1868) and 15th (1870) Amendments. Unfettered racism fueled their outrage at the notion that Black men would have a say in politics when white women did not. They refused to support the 15th Amendment as part of a piecemeal approach to securing suffrage for all, and they actively campaigned against it. Stanton and her supporters partnered with pro-slavery Democrats in what became known as the Southern Plan in which they pushed for the enfranchisement of (white) women on the premise that they would deliver the votes necessary to defeat the 15th Amendment. The Woman Suffrage Movement fractured into two organizations that didn’t unite until after passage of the 19th Amendment 50 years later.

2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which granted many women the right to vote. The amendment forbid denying the vote to anyone on the basis of sex and was an important milestone in the Women’s Suffrage Movement that began 72 years earlier. But the amendment, like the movement, was far from perfect; the 19th Amendment did not give Black women, Latinas, American Indian women, and Asian American women the right to vote because it did not include race as a protected classification. Racist policies and institutional practices continue to make access to the ballot a challenge for many People of Color.

Women like Ms. Andrews used their pens, their voices, their time, and their bodies to advocate for women’s suffrage and a voice equal to men in the policies, laws, and people who governed them. Many understood the vote as essential to furthering their work for other causes, including social change, access to education, and equal employment opportunities. They understood the 19th Amendment was not the end of women’s activism, it was the beginning. In the 100 years since the amendment was passed, women have continued to advocate for issues that affect their families, their communities, and the nation.

Votes for Women: 100 Years of Change opened at the Ohio History Center in Columbus, Ohio, in February 2020 less than three weeks before the museum closed temporarily in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ms. Andrews’s parade blouse and jacket and two of the three suffrage sashes are featured in the exhibit Votes for Women: 100 Years of Change at the Ohio History Center. Like the traveling exhibit upon which it is based, the exhibit privileges Ohio women’s voices and provides a platform for them to continue their advocacy. It asks six questions: Why is the vote so important? What does voting give you power to do? How do you speak out? How do you experience discrimination? What other issues do you work for? And finally, what does more than 100 years of women’s activism make possible?

The exhibit makes clear that Ohio women were a formidable force for change. And they’re not done yet. These women who fought for abolition, suffrage, civil rights, and anti-discrimination laws for housing and employment paved the way for new waves of activism for the LGBTQ+ rights, Black Lives Matter, and Indigenous People’s rights movements happening today. Some of these women are politicians, judges, public speakers, and writers, but others, like Mary Andrews, are relatively unknown outside of their communities. They step up and speak out day after day, exposing themselves to criticism, insults, slander, and vicious verbal attacks and violence or threats of violence against themselves and their families.

Ohioians continue to advocate on behalf of themselves, their families, and their communities on a wide range of issues. Many of them look to the next generation to continue to their fight.

In 2020 we commemorate—not celebrate—the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment to highlight the tremendous impact Ohio women have had on their communities and the state while also acknowledging the movements’ mistakes, the amendment’s exclusions, and the great deal of work still to be done to achieve equality. Ohio Women Vote invites you to explore Ohio women’s experiences as activists in their own words and to think about how you might join them to shape the future (while the Ohio History Center is closed, you can experience the traveling exhibit online here).

Dr. Odom is a history curator and manager of the Curatorial Department at the Ohio History Connection.