4-H Collections: Sewing

The Ohio History Connection seeks to shine a spotlight on 4-H and the hard work of Ohio young people by highlighting 4-H collections.

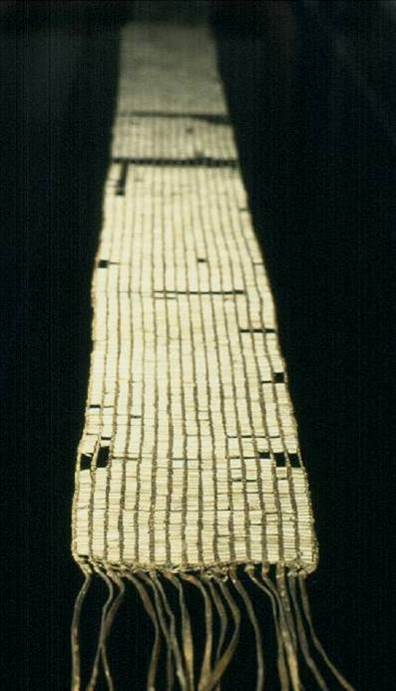

In the current issue of the Journal of Ohio Archaeology I have a paper in which I review “early historic American Indian testimony concerning the ancient earthworks of eastern North America.” I summarize my conclusions in my August column in the Columbus Dispatch. I began collecting historic-era American Indian perspectives on the ancient earthworks in order to inform my research on the Newark Earthworks. In building my arguments for the former existence of a Great Hopewell Road, for example, I referred to a Delaware/Lenape tradition about a belt of white wampum that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific and served as a “white road” upon which people could travel “safe from attack.” I think it’s possible that this “white road” is a metaphor based upon a dimly remembered tradition relating to an actual long, straight, parallel-walled road, such as the one that extended from Newark an undetermined distance in the direction of Chillicothe. This Great Hopewell Road may have been a conduit for pilgrims bearing offerings if not from the Pacific, then at least from the Atlantic coast in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west — the extent of the so-called Hopewell Interaction Sphere.

So, while my Journal of Ohio Archaeology paper concludes rather pessimistically that there are no documented early American Indian traditions that speak reliably to the original purpose and meaning of the ancient earthworks, there is no reason to believe that traditional stories of contemporary tribes with historic roots in the eastern Woodlands could not include themes and elements that echo, if faintly, traditions of the Hopewell culture. And if that’s conceivable, and I think it is, then it would be worthwhile to look for them. Indeed, the late Robert Hall argued persuasively that such elements are present in the traditions of many American Indian tribes: “The historical past was real, but the evidence that survives of it can be distorted and disconnected, like a shadow cast on a field of rocks. The evidence includes traditions often imperfectly transmitted between generations; ceremonies whose symbolism has changed to become supportive of new values; origin myths naturalized to new locations; ceremonial objects whose full significance was known only to elders who have died; the bones of Indians whose deaths silenced personal stories that still await telling; buried artifacts that speak of technologies long forgotten; and earth constructions that speak of rituals long abandoned. …Cultural objects and preserved traditions can tell stories beyond count when they are approached like respected elders and their mysteries sought out.”

In the good old times, before any European had landed on their shores, the Lenape had a string of white wampum beads…which stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and on this white road their envoys traveled from one great ocean to the other, safe from attack. Rev. Albert Seqaqknind Anthony, Delaware Indian, 1890

One reason why its important to take seriously what American Indians have had to say about the earthworks is that they may offer explanations for these sites that might not have occurred to archaeologists, but which can be treated as hypotheses to be tested against the archaeological data. As an example, one of the most common interpretations for earthworks in the list of oral traditions I’ve compiled is that they were fortifications. That was a popular idea among early antiquarians, but there hasn’t been much if any archaeological evidence to support it. Relatively recent investigations at the Pollock Works, however, may provide confirmation that at least one of these ancient earthworks actually did, for a brief time, serve as a fort. And, as I suggest in my paper even a brief military episode at such a site, regardless of its broader socio-political impact, might have figured prominently in the oral traditions of the group much as the exploits of Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie have loomed so large in the history of the Alamo Mission. Brad Lepper For further reading: Hall, Robert 1997 The Archaeology of the Soul: North American Indian belief and ritual. University of Illinois Press, Champaign. Lepper, Bradley T. 1995 Tracking Ohio’s Great Hopewell Road. Archaeology 48(6):52-56.

Notifications