The stone chimney of the Tarr Log House.

It’s an old joke: I’m an archaeologist. My career lies in ruins. Its amusing (at least the first time you hear it) and its true. For the most part, we study ruins. Gordon Willey, in his famous work on prehistoric settlement patterns in Perus Viru Valley, wrote that the material remains of past civilizations are like shells beached by the retreating sea. The functioning organisms and the milieu in which they lived have vanished, leaving the dead and empty forms behind. The challenge of archaeology is, of course, how to reconstruct the functioning society from the dead and empty forms that remain. For historic sites there is much more of the social context available in written records of various kinds, which are not available to archaeologists’ studying pre-literate or non-literate societies. Archaeologists Elizabeth Graham, David Pendergast, and Grant Jones, writing in the journal Science, made the point that “the stature of the written record will always dwarf the stratigraphic one. The former is a direct product of thought; the latter, a product of decay and destruction, is what people thought would never happen.”

Mayan stela from the site of Copan.

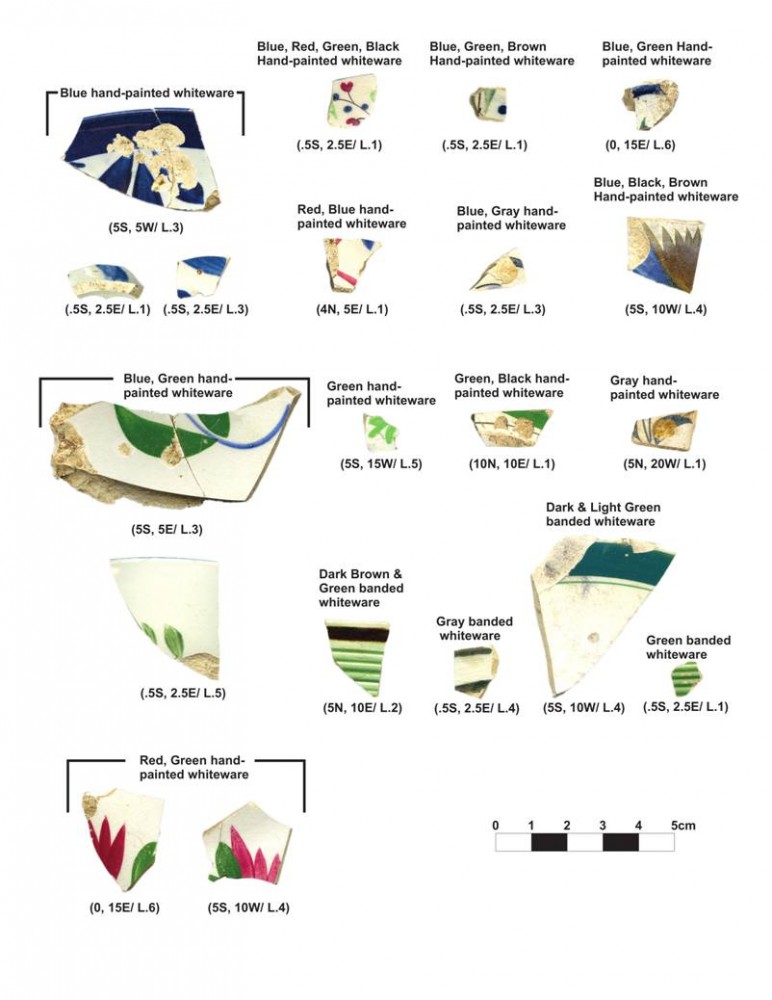

The archaeological (stratigraphic) record does have certain significant advantages over the written record. For one thing, it has a hugely longer reach into the past than history and, as I point out in my October column in the Columbus Dispatch, it is not biased by human motivations: garbage doesn’t lie. So an archaeological investigation of historic era sites can supplement or revise what we thought we knew from a reading of the written record. In my column, I describe the recent discovery and study of the Tarr log house in Jefferson County by the Cultural Resource Management firm PAST Professional Archaeological Services Team. Craig Keener and his team show how bits of broken crockery and their distribution across the site can tell the story of one family’s decline from social prominence to the hoi poloi. The early nineteenth century garbage includes sherds of very fine pottery sure signals of high status. The late nineteenth century garbage deposits are dominated by plainer, less refined varieties more typical of middle class families. The magnificent sandstone block chimney, the most prominent surviving remnant of the Tarr log house, reminds me of an ancient Mayan stela standing amidst the ruins of a long abandoned city. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s wonderful poem “Ozymandias” describes a “colossal Wreck” on another continent bearing testimony to the fall of a proud tyrant. The Tarr log house is an Ozymandian ruin writ small. It is an object lesson in “what people thought would never happen,” but which inevitably will happen to every society’s palaces, temples, or tenements. At least, so far, it has been inevitable. If we succeed in learning from the ruins of our past, perhaps we can find a way to escape the fate of all those civilizations that have gone before. It could happen. In their North American Archaeologist article, Keener and his co-authors acknowledge Ohio American Energy, Inc. for funding “the surveys of the site and curation of the artifact assemblage.” The collection is curated here at the Ohio Historical Society.

Examples of high status ceramics from the Tarr Log House. Image courtesy of Craig Keener.

For further reading:

Graham, Elizabeth, David Pendergast, and Grant Jones 1989 On the fringes of conquest: Maya-Spanish contact in colonial Belize. Science 246:1254-1259. Keener, Craig S., Kevin Nye, and Joshua Niedermier 2013 Archaeology of the Tarr Log House: an historic farmstead in eastern Ohio. North American Archaeologist 34(1):1-47. Brad Lepper